Nature, Crisis, Consequence: Using the Past to Rethink Environmental Change

By Cecilia Cassidy, CAS ‘25 & Common Home Editor

Image of the painting The Course of Empire by Thomas Cole, 1834. It illustrates a Roman column and part of a Roman temple on rocks around a body of water. Photo provided by Cecilia Cassidy

With every passing year, the world breaks heat records. The oceans continue to rise, and our carbon footprint continues to grow. Even worse, many of our institutions barely address the impacts of climate change. However, museums and cultural institutions are starting to fill this gap by putting climate change at the center of their work. The New-York Historical Society on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, one of New York’s oldest yet most relevant museums, has done so with the exhibit Nature, Crisis, Consequence.

On view from late March to mid-July of 2023, Nature, Crisis, Consequence comes from the mind of Wendy Nālani E. Ikemoto, the museum’s Senior Curator of American Art. The exhibit was separated into four sections, each displaying the work of artists of various backgrounds and mediums with the overall aim to explore “the social and cultural impact of the environmental crisis.”

Upon initial examination, the range of topics and artists’ voices in the exhibition may seem incohesive. For example, the first section, “The Environment: Ruin and Resilience,” features Thomas Cole’s The Course of Empire. This five painting series illustrates the development and fall of civilization, from a lush green mountain and a lonely building to a deserted city of overgrown ruins. Cole suggests that in the end, the environment is “ultimately triumphant over humankind’s ability to tame it.”

In the “Environmental Racism, Environmental Justice” section, viewers observe an empty turquoise ceramic basket by artist Courtney M. Leonard. “As the artist explains, her fragile woven earthenware forms speak to the inability of the natural environment to withstand the impact of manmade systems and infrastructure,” shares the museum. Leonard’s attitude towards environmental change clearly opposes that of Cole’s, depositing conflicting messages in viewers’ minds.

However, this dissonance is intentional.

It recognizes the different attitudes Americans have towards the environment and climate change— particularly over generations. For instance, Leonard’s sculpture was made in 2015, reflecting an environment vastly different from the newly industrial world of the 1830s influencing Cole’s The Course of Empire. By showing where our relationship with the environment started and where we are now, Curator Ikemoto creates conversation about the direction our relationship with the planet should move in.

Ikemoto takes an active role in bringing the disharmonious voices into direct conversation— at times, quite literally. In the section entitled, “The Railroad: Speeding Settlement,” the main wall features three paintings: a large landscape sandwiched between two portraits. The landscape is Donner Lake from the Summit by Albert Bierstadt; created in 1873, this painting celebrates the completion of the transcontinental railroad through the rugged West just four years before, calling to mind the idyllic age of expansion and industrial America. Notably, however, the painting excludes the narratives of the people displaced and the crimes committed along the way. In striking nearness, artist Ben Pease’s portrait Ishbinnaache-Protector, Crow Scout Curley (2020) hangs left, responding with remembrance and resistance.

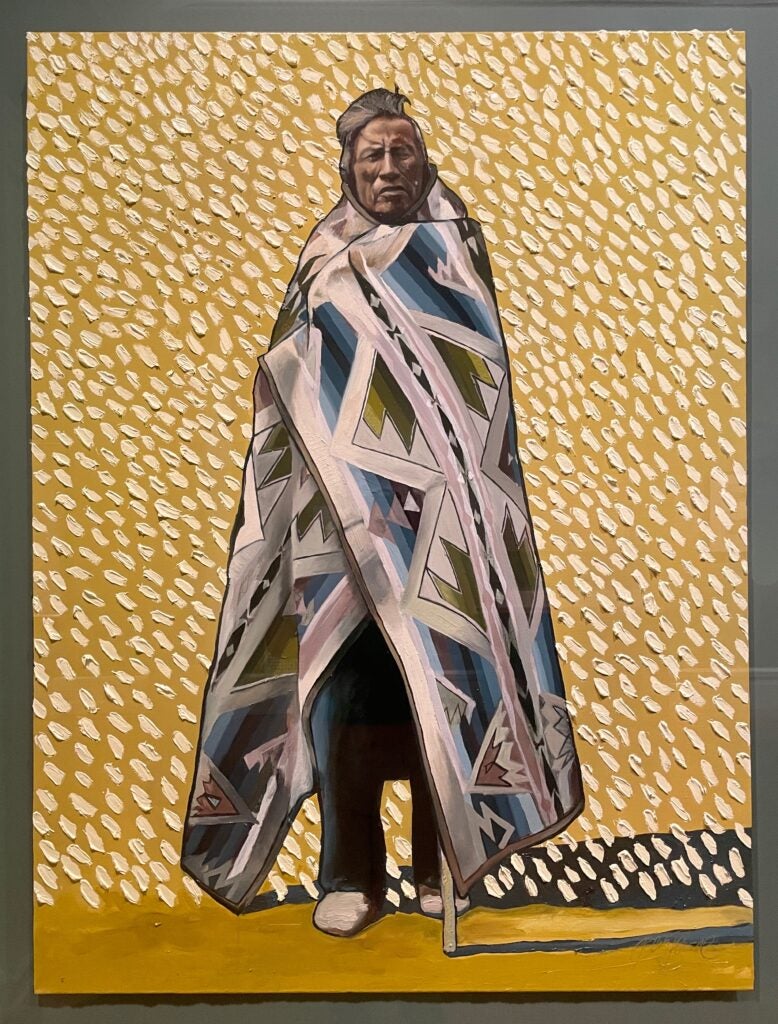

Image of the painting Ishbinnaache- Protector, Crow Scout Curley by Ben Pease, 2020. It illustrates a Apsáalooke man standing wrapped in a colorful blanket against a yellow background with white splotches. Photo provided by Cecilia Cassidy

It features Ashishishe, a member of the Apsáalooke and a scout for the U.S. in the Sioux Wars, wrapped in a patterned blanket against a yellow background with white dots. The dots represent “incoming adversaries,” like the U.S. government, which later seized almost 95% of Apsáalooke land, mainly for the construction of the railroad.

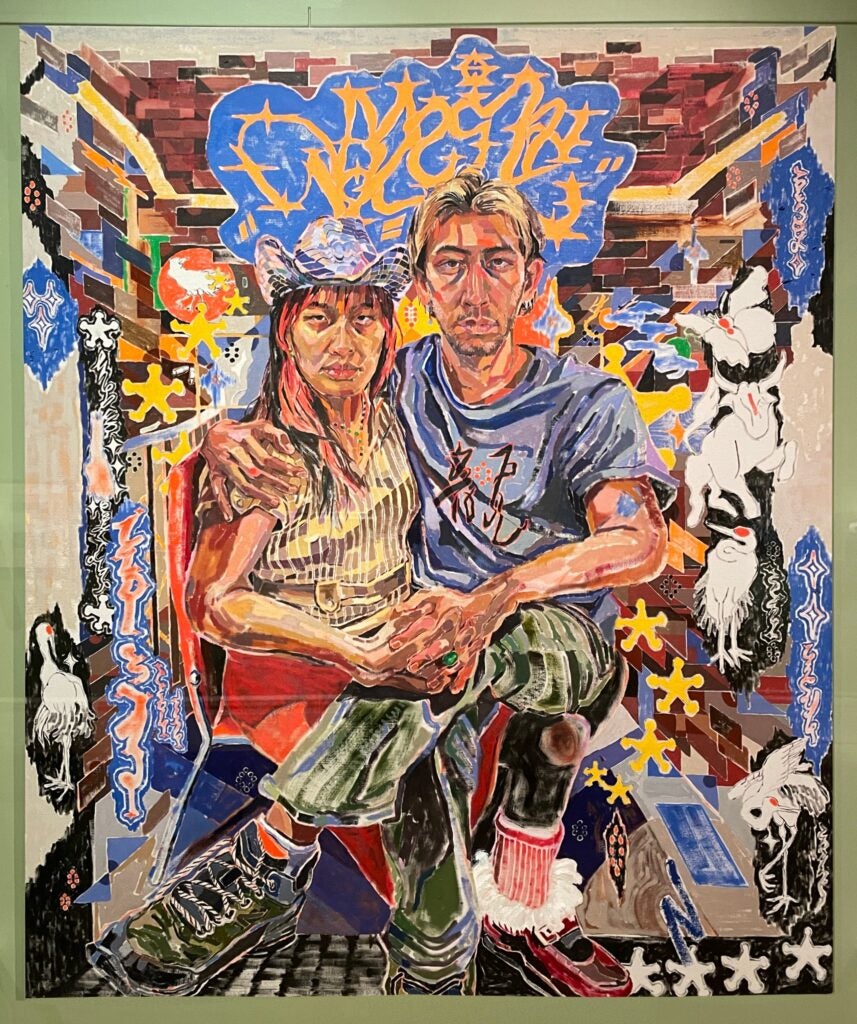

On the right, Oscar yi Hou, an artist from the U.K., communicates similar themes with his portrait of a Chinese-American woman dressed as a cowgirl sitting with a Chinese-American man, titled Far Eastsiders, aka: Cowgirl Mama A. B & Son Wukong (2021).

Image of the painting Far Eastsiders, aka: Cowgirl Mama A.B & Son Wukong by Oscar yi Hou, 2021. It illustrates a Chinese American woman wearing a cowboy hat and a Chinese American man against part of a colorful brick wall. Photo provided by Cecilia Cassidy.

Hou hopes to bring more recognition to the Chinese immigrant laborers who were essential to the construction of the railroad, but are often left out of the history and imagery of the American West. Pease and Hou’s contemporary perspectives give viewers the rare opportunity to reexamine older pieces, revealing the devastating hidden environmental cost of technological advancement.

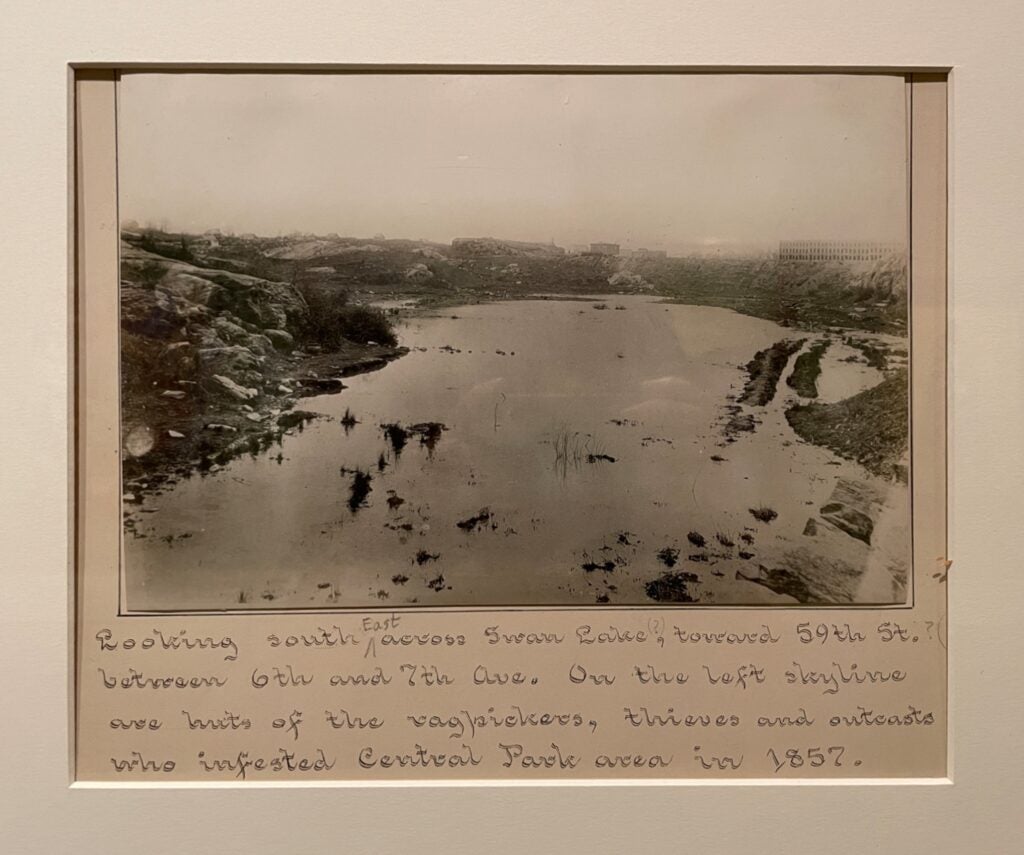

Across the hall, the section “Seneca Village: Central Park, at What Cost?” uses historical artifacts to highlight another story of the land seizure, change, and minority displacement behind an American gem. Seneca Village was a predominantly African American community that resided between the West 80 streets of Manhattan in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was taken over and cleared by the state of New York in order to build Central Park. While this section’s focus is seemingly niche in comparison to the rest of the exhibit, it underscores how Nature, Crisis, Consequence wants viewers to expand their understanding of environmental change from an altered landscape to the way our communities are affected by displacement and blatant racism.

Image titled Looking southeast across Swan Lake…, ca. 1858. It shows rural land in Upper Manhattan in black and white. Photo provided by Cecilia Cassidy

In addition to the works of art themselves, Ikemoto incorporates the ethos of the museum as a historical society with her inclusion of important legislation and historical context on plaques. This information challenges the assumptions with which many viewers enter the exhibit. It also aligns with the New-York Historical Society’s overall goal to include and highlight more diverse perspectives in their institution.

Nature, Crisis, Consequence excels at showing the impact of environmental change on people, especially those who have been historically marginalized. Ikemoto even includes contemporary voices in the exhibit from an unexpected source— visitors. She invites viewers to leave a note in the comment book by the exit before they leave the exhibit. One visiting family wrote: “Our visit has been moving, the art inspires, raises questions, sometimes wounds.”

And they’re right. The exhibit takes the vastness of environmental change and situates it in the harmful decisions humans have made in the past two centuries. This realism and nuance— not overwhelming fear or hope— is what motivates the viewer to keep moving amid the climate crisis once they step back on to Central Park West Street.