A Field Trip to Okinawa

Professor Onoda Power brings the endangered animal to a virtual stage – in the shadow of a US military base

Author: Marion Cassidy, COL ’23 & Common Home Editor

Creating virtual community experiences has been quite a challenge throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. Particularly for theater, which gains so much of its impact from the in-person experience, engaging audiences has been difficult over Zoom. Yet Professor Natsu Onoda Power seems to have the secret.

In her show “Okinawa Field Trip,” which premiered at the tail end of the 2021 spring semester in the Georgetown Theater and Performance Studies Department, Power engaged her virtual audience by using theater to highlight environmental concerns. The interactive Zoom play touched on US-Japanese relations as well as the resulting environmental destruction.

Natsu Onoda Power originally planned to create a play about Okinawan music during her Fall 2019 sabbatical in Japan. She sat in on classes at the Okinawa Prefectural University of Arts and met local artists. As soon as she arrived, she noted she was “really struck by the issues that I had never thought about before, primarily, the US military presence in Okinawa and its history with Japan that’s characterized by so much colonialism.” The longer Professor Onoda Power stayed in Okinawa, the more she realized she wanted the project to focus on the Okinawan people.

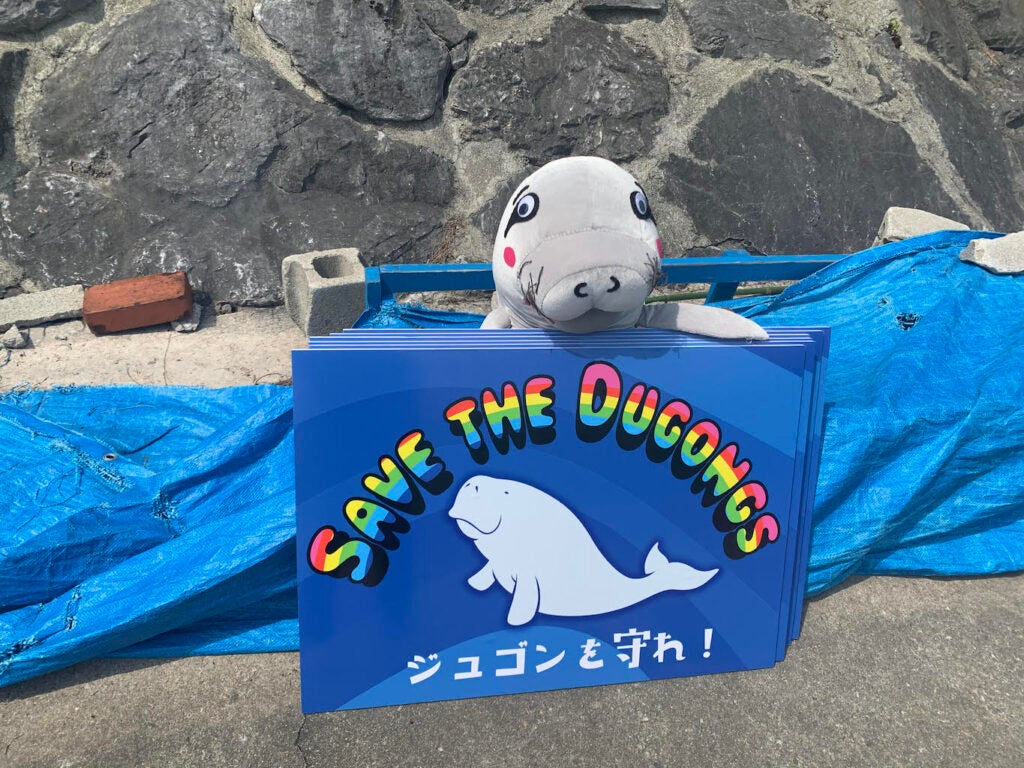

Each performance of the play was considered a “field trip.” Audience members toured Okinawa virtually by seeing different sites around the city, talking with fellow students on the trip in breakout rooms, and even learning about the native food, with a dugong named Doug as their leader. Dugongs – a marine animal in the manatee family – are an endangered species and an Okinawan cultural icon.

There are many folkloric legends about dugongs and they are symbolic of the natural environment and biodiversity in the area. The construction of an American military base was so dangerous to the small dugong population that the Okinawan dugong, along with environmental advocacy groups, were actually plaintiffs in a United States court case against the U.S. Department of Defense filed in 2003 (the dugong was later dismissed as a plaintiff because animals have no standing under the National Historic Preservation Act under which the case was filed).

The American military bases and endangerment of these dugongs is still a point of contention today. Onoda Power does not shy away from bringing up these issues in her art. As the play proceeds it’s clear Doug and his fellow dugongs have incurred trauma due to the American military presence in their environment including the destruction of Doug’s community and family separation.

The incorporation of the local Okinawans’ environmental knowledge was vital to the play. Onoda Power explained, “I just don’t think you can do anything about a place without the people there, I think it would be wrong to do that and that’s something that I’m really passionate about. I love listening to people’s stories and I could not have done this project without the support of my Okinawan friends.”

Anthropologist and Okinawan native Hideki Yoshikawa was an instrumental member of Onoda Power’s research team. For instance, he noticed in the first version of the script Doug ate seaweed, when in actuality, dugongs eat seagrass. It’s this attention to details and local culture that make this play so special.

Yoshikawa grew up in Okinawa and completed his education in the United States. His unique background allows him to help advocate for his hometown’s environment. Yoshikawa shared that the impact of the bases on Okinawa is so significant that locals grow up knowing about the ‘base issue.’ He said, “the Okinawan environment is so rich, we have so many endangered species at Henoko-Oura Bay (where the U.S. and Japanese governments have tried to build a base), and we thought ‘hey they can’t build a base here,’ now I am here after 20 years still fighting and it’s been very difficult.”

Aside from scientific or historical knowledge, those who worked on the project felt a personal impact as well. Yoshikawa said, “being a part of this experience has been pretty reflective, it’s sort of debuting what I’ve been doing. I feel like I have a renewed spirit for another fight and it has encouraged me to seek more creative ways of being an anthropologist.”

I just don’t think you can do anything about a place without the people there.

Onoda Power

An unlikely consequence of the pandemic was that people everywhere were able to experience the ongoing conflict in Okinawa due to the virtual nature of the show. Onoda Power certainly faced many difficulties. Due to the time difference, she taught class at 3:00am and lived in ten different locations throughout the pandemic. Once conditions were safe, she started live streaming from environmental protests to her peers in the States, which was the lightning bolt moment that made her realize she could do her play virtually as well.

The virtual nature also allowed Okinawans and Americans to collaborate on this project – a true embodiment of our 21st century, globalized and connected world. Onoda Power concluded, “every theater performance is a flawed project because it cannot possibly be a perfect product, but I really do think that the greatest value of this project is in our field trip.”