The Devil and Gaia

Film Reviews of the DC Environmental Film Festival

Authors: Maya Snyder & Alannah Nathan, both SFS ’24 & Common Home Editors

The DC Environmental Film Festival aims to educate, inspire, and incite environmental action through the power of film. This year marks its thirtieth anniversary. Our editors at Common Home reviewed two of this year’s featured films: Going Circular and Devil Put Coal in the Ground.

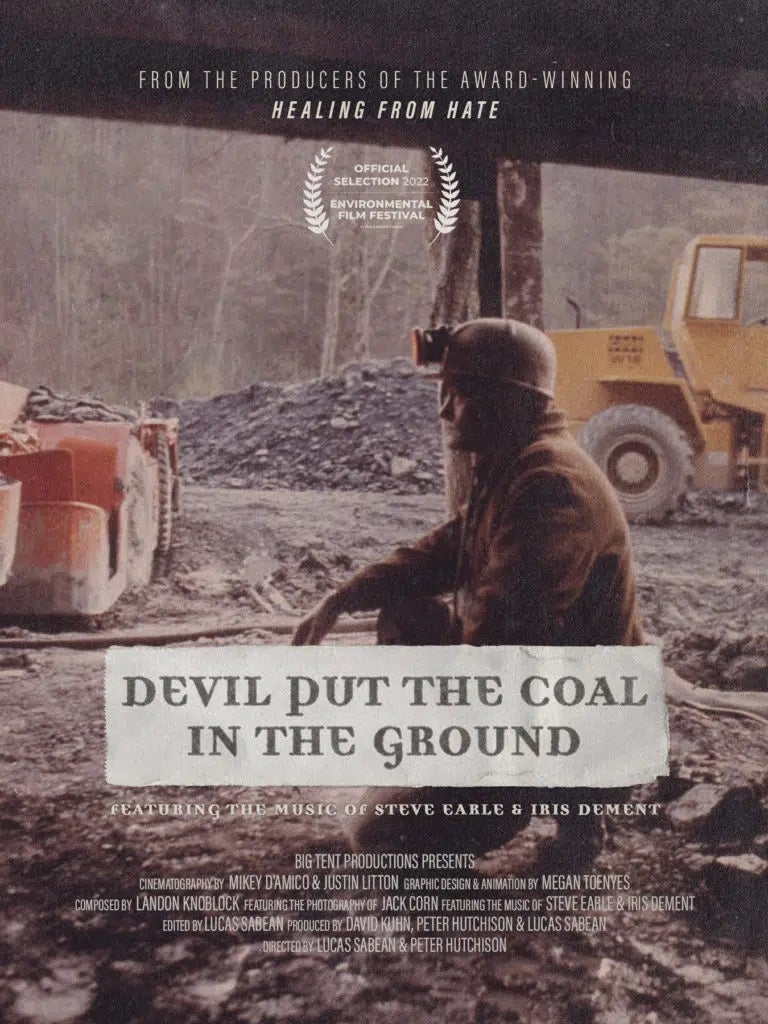

Devil Put Coal in the Ground (2021)

Directed by David Hutchinson & Lucas Sabean; 2022 Winner of DCEFF Audience Award for Best Feature Film

“If coal was the future of the country, and it was so good for this state, why is Boone Country one of the poorest in the nation?” asks Lisa Henderson, a West Virginian mother. For decades, the U.S. has capitalized off the energy-abundant and environmentally-destructive fossil fuel. The communities that mine the coal, however, often see little of its benefits and all of its costs. Told from the personal stories of West Virginians, Devil Put Coal in the Ground documents the rise of big coal corporations and the devastation of Appalachia mining communities.

For many families in West Virginia, coal has been a part of their lives for generations. However, today’s coal mining communities look very different than they did thirty years ago. The film shows thriving coal mining communities in the years before the 1970s, the peak of union membership.

A turning point came in the early 1990s when big coal corporations like Massey Energy grew in power and restricted union activity. They soon cut wages. Families that had been relatively stable financially started to struggle. Many community members left in search of better opportunities.

The town became almost unrecognizable. “It’s eerie because it feels almost like an atomic bomb went off,” said Henderson of the drastic changes in her hometown. “Once it had life. Now it’s gone.”

As large coal companies continued to dominate the West Virginian coal industry, environmental conditions rapidly deteriorated. To remove larger quantities of coal more quickly and cheaply, coal corporations turned to more invasive techniques. Mountaintop removal– where explosives blow apart mountain ridgelines – became an increasingly popular method of coal mining. Appalachia’s distinctive landscape was changed forever.

Coal has had serious effects on West Virginians’ health. Parents and other residents began raising concerns when children attending an elementary school a mere 400 yards from a Massey Energy subsidiary coal processing plant began exhibiting health problems.

At one point, the film followed Paula Jean Swearengin, a West Virginian politician, driving through a residential neighborhood as she pointed out house after house that belonged to someone who had cancer. While driving through these “unexplainable cancer clusters,” she expresses her despair of so much loss in her community. “To lose my daddy at fifty-two, that’s not fair. To see my neighbor’s children get cancer, that’s not fair,” Sweregin said. “My biggest fear is that one of my children will get cancer. This isn’t worth it.”

The film also exposes ties between the coal industry and the opioid epidemic that is ravaging the state. The coal industry and big pharma are symbiotic, asserts Bob Kincaid, an activist and local West Virginian. He adds, “Beyond this physical world of devastation is internal, spiritual, psychological devastation– and they come from the same place.”

“Beyond this physical world of devastation is internal, spiritual, psychological devastation– and they come from the same place.”

Activist Bob Kincaid

However, opposition to coal companies remains controversial in West Virginia. In a community eager to attract jobs and rebuild the economy, corporations are given relatively friendly treatment, often resulting in concerns being swept under the rug. Moreover, because of coal’s long history in Appalachia, coal remains central to many people’s livelihood. And yet Lisa Henderson notes, “There’s a difference between being a friend of a coal miner, and a friend of coal.”

Devil Put Coal in the Ground captures the anger, frustration, and sadness felt by West Virginians witnessing the environmental and emotional devastation of their community. At the same time, the film paints a powerful picture of resilience, showcasing members of the community who continue to fight for their children, their mountains, their home.

Going Circular (2021)

Directed by Nigel Walk and Richard Dale

In 1972, James Lovelock proposed that all systems – living and nonliving – are connected in one vast, self-regulating system. His big idea – The Gaia Theory – suggests each living organism plays a role in defining and maintaining the conditions for life on earth. Today, as a result of unhinged consumer culture, unquestioned economic assumptions, and perceived distance with nature, humans have knocked that system out of balance. In our quest for modernity, we’ve forgotten that we’re part of the Earth system, not separate from it.

“Going Circular,” directed by two-time Emmy nominees Nigel Walk and Richard Dale, imagines a circular economy future in which humans work with nature, rather than against.

Today’s 21st century economy is linear: we follow a “take-make-dispose” step-by-step plan. We extract materials from the ground, produce single-use goods, distribute them around the globe, then consume them, with little thought of where they come from or where they’ll go once we use them. Our model of consumption is in complete contrast with nature’s natural system of renewal. In nature, the waste of one system is the energy of the next system. There is no such thing as waste.

The promises of a circular economy are extensive. What if we widely adopted biomimicry, the practice of using nature as a model for human inventions? As the film notes, “The truth is, natural organisms have managed to do everything we want to do without guzzling fossil fuels, polluting the planet or mortgaging the future.” For example, one company, spotLESS Materiels uses sprayable coatings that repel liquid and bacteria by using materials inspired by the same physics as the Nepenthes pitcher plant.

“The truth is, natural organisms have managed to do everything we want to do without guzzling fossil fuels, polluting the planet or mortgaging the future.”

from Going Circular

Or, the film provokes us to ask, what if we harnessed the potential of 3-D printing to reduce waste – from our homes to factories? For example, Ford and HP have collaborated to create a printer that recycles waste into automotive parts.

The questions abound: What if we rethought our food systems in a way that deliberately ensured zero-waste? Or used fabrics that could be used and reused over and over?

A circular economy could reduce 90% of wasted materials. Today, the economy is only about 8.6% circular. Doubling our circularity would cut CO2 emissions by 39% by 2030. Moreover, the circular economy could result in $4.5 trillion in economic growth.

In the words of James Lovelock, “We live on a live planet that can respond to the change we make, either by canceling the changes or by canceling us.” We are at a critical turning point in which we must change the way in which we live, starting with the way in which we consume.