Defense, Denial, and Disinformation: Uncovering the Oil Industry’s Early Knowledge of Climate Change

By Charlotte Taylor, SFS ‘24

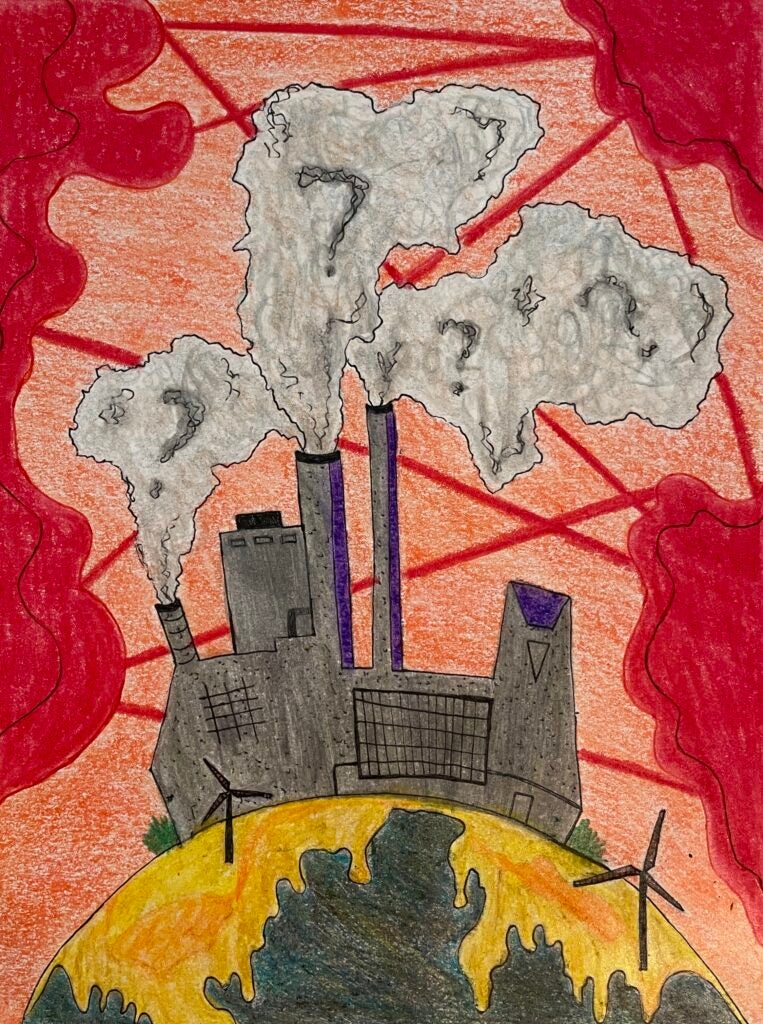

Illustration by Cecilia Cassidy

As early as 1959, oil industry executives understood the connection between burning fossil fuels and climate change. Soon thereafter, industry scientists confirmed beyond a reasonable doubt that the burning of fossil fuels contributed to anthropogenic climate change. In response, oil companies scrambled to promulgate climate change denial and disinformation in order to avoid government regulation. It was not until the late 1990s and early 2000s that oil companies began publicly acknowledging the scientific consensus on climate change and responded by promoting market-based solutions to mitigating emissions.

Popular concern for anthropogenic climate change did not emerge until the late 1980s, but formerly secret industry documents that are now available through the Climate Files database reveal that oil industry scientists were raising concern about oil’s impacts on the climate as early as the 1950s and 1960s.

Starting in the 1950s, the oil industry designated funds to research the effects of pollution on the environment. For example, the 1954 American Petroleum Institute (API) article “The Petroleum Industry Sponsors Air Pollution Research” suggested that smog was the product of a reaction of ozone and gasses that evaporate from cracked gasoline.

Later, Shell’s 1959 article “The Earth’s Carbon Cycle” affirmed that burning fossil fuels released 2.5 billion tons of carbon each year at the time and “might conceivably change the climate.” Nonetheless, the paper’s author, Dr. M. A. Matthews of Shell International Chemical Company employed just enough doubt to cast uncertainty on the suggested climatic threats. Matthews’ doubtful rhetoric appears to be the first of many industry ploys to instill uncertainty in the public and generate distrust in scientific fact.

Moreover, documents reveal that the API was privately informed about the threat of climate change by its commissioned Stanford Research Institute scientists. In the scientist’s report, “Sources, Abundance, and Fate of Gaseous Atmosphere Pollutants (Prepared for the American Petroleum Institute),” Elmer Robinson and RC Robbins write that if fossil fuel production continues, “Significant temperature changes are almost certain to occur by the year 2000” which “could bring about climatic changes.” In direct and convincing language, the scientists declared that “there seem[ed] to be no doubt that the damage to our environment could be severe.”

This means that at the latest by 1968 (when the report was published) the oil industry knew beyond reasonable doubt about the relationship between burning fossil fuels and climate change.

“By 1968…the oil industry knew beyond reasonable doubt about the relationship between burning fossil fuels and climate change”

The “1988 Exxon Memo on the Greenhouse Effect” took a similar stance. While acknowledging the severity of the greenhouse effect, the policy memo ordered Exxon to “emphasize the uncertainty in scientific conclusions” and “resist the overstatement and sensationalizing of potential greenhouse effect which could lead to noneconomic development of non-fossil fuel resources.”

Moreover, the history of the Global Climate Coalition (GCC) serves as a prime example of the oil industry’s collective efforts to spread climate disinformation. The GCC mobilized funds to oppose greenhouse gas regulations through collaboration across automotive, manufacturing, mining, and petroleum industries. In the coalition’s testimony before the Energy and Power Subcommittee of the House of Representatives, Michael E. Baroody testified that a natural greenhouse effect exists, however adding that “there is still substantial uncertainty about the importance of human-induced global warming.”

The accompanying GCC report even claimed that “some scientists forecast that the impact of future climate change may be neutral or beneficial.” Ultimately, the GCC and oil industry executives weaponized doubt of climate change to protect their businesses from environmental regulations.

Prompted by a strengthening consensus among the scientific community and growing concern among the public, in the late 1990s and early 2000s, big oil began making public concessions to climate science and hinted at a commitment to mitigating the threats of climate change. Still, these concessions were characterized by a hostility towards government regulations. Instead, the industry promoted voluntary solutions based on technology and economic benefits.

Take for example, Shell’s 1998 Report, “Climate Change: What does Shell Think and Do About It?” In this report, Shell acknowledged the connection between climate change and the burning of fossil fuels. However, instead of pledging to reduce its carbon emissions, Shell claims it will combat climate change by continuing to produce oil and gas in order to fuel economic growth and foster technological innovation. In 2000, Exxon reiterated such market strategies, claiming “technology will reduce the potential risks posed by climate change.” This response from Shell proved ineffective at best, and harmful at worst; it ignored any sense of responsibility in the company’s direct contributions to climate change. Instead of addressing the climate change problem head on by reducing carbon emissions, the oil industry favored nonbinding, technological and market-based steps to confronting the issue.

Now, we are left to deal with the environmental consequences of years of corporate-backed denial which has helped instill public distrust in climate science despite the strong agreement among scientists. Today, this climate denialism appears in a new form: corporate greenwashing. Greenwashing is when a company misrepresents its products or services to be more environmentally friendly than they are in order to gain sales. It functions as a marketing tool that tricks the public into thinking their purchase at a certain company is better for the environment. In reality, these companies – not unlike oil and gas corporations – are doing little to nothing to actually combat climate change.