Does Nature Have Rights?

Sadie Morris, SFS’22 & Common Home Editor with Hope Babcock, Professor of Law and Director of the Institute for Public Representation at Georgetown

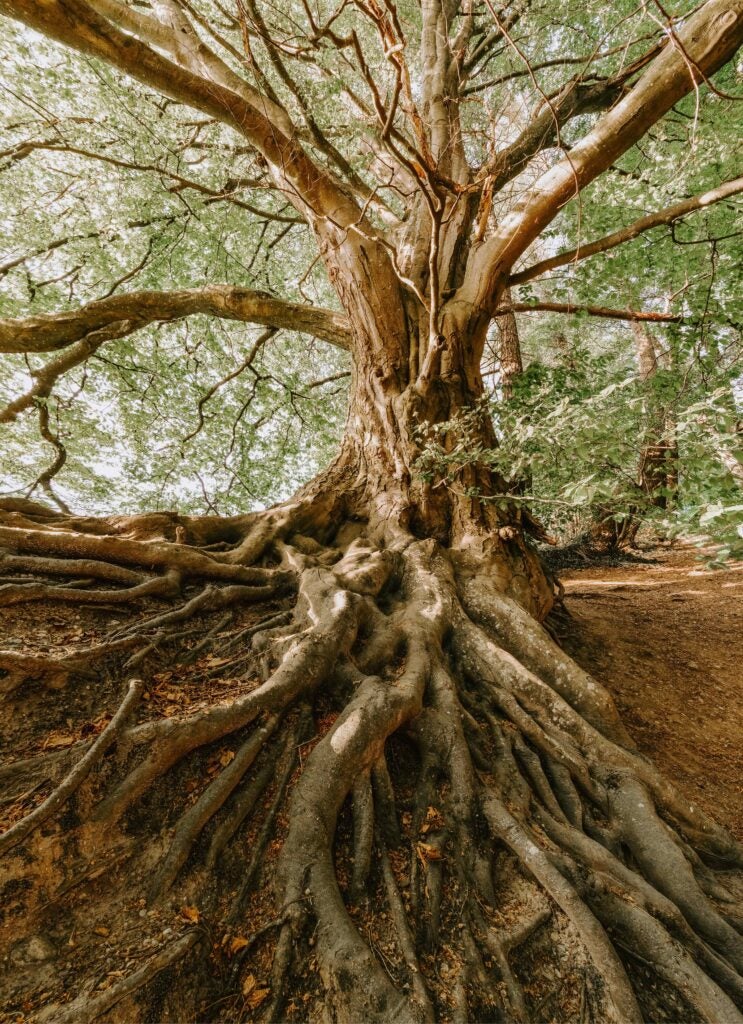

Looking out on a sea of sleepy-eyed first-year law students in his University of Southern California property class, Professor Christopher Stone posed the question for which he would become famous, mostly just to keep his student’s foreheads from hitting the desks: Should trees have legal standing?

This was a revelatory question because in the U.S. an entity must be able to prove standing in order to bring a lawsuit. It’s historically reserved for humans and the human-adjacent, not trees. Standing is a legal doctrine adapted from English common law and enshrined in Article III of the U.S. Constitution.

A party may only bring a lawsuit if they demonstrate that they personally have suffered actual or threatened injury that can be traced to an action by the opponent party. When it comes to cases involving threats to natural features (such as trees), litigants (humans) traditionally must prove some connection between themselves and the threatened resource.

For example, if someone wanted to stop the dredging of a wetland by applying the Endangered Species Act, they would have to demonstrate that harming the wetland ecosystem would affect their own quality of life, such as through losing enjoyment of the land. This connection can be hard to prove.

At its core, an irreparable natural phenomenon would be threatened primarily, more than a secondary, constructed impact on humans. It often requires imagination, and turns of logic, for a litigant to place their own detrimental impact at the center.

Even as environmental lawyers rejoiced at the passage of major legislation in the 1970s, such as the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and the Endangered Species Act, that opened the courts to suits meant to protect the environment for generations to come, their actual efforts have continuously been stymied by the failure to prove standing; environmental cases are consistently thrown out of court before the merits of the case are even heard.

To avoid this legal dead end, Professor Stone argued that instead of trying to finesse a way for humans to prove standing on behalf of nature, nature itself should be recognized as an entity that could bring cases. After all, the actual injury to nature is able to be proven scientifically and is often even visible to the naked eye.

Instead of trying to finesse a way for humans to prove standing on behalf of nature, nature itself should be recognized as an entity that could bring cases.

Traditionalists argue that opening the door to “inanimate objects” such as rivers, wetlands, and trees, would open the doors of the court for anything to walk through (though not literally of course). Moreover, a view of nature that imbues natural beings with legal standing would represent a dramatic reconceptualization of the relationship between humans and nature. Such a view would put the two on an even footing. Lawyers unprepared to see such a radical transformation take place within one of the most conservative institutions in the United States argue that the proper venue for such arguments is within the political realm of the legislative branch.

In fact, the more far-reaching cultural question of personhood for nature has been a political and social question central to Indigenous struggles for decades. Legal battles around standing have played out only a few times in U.S. courts: namely, in the 1972 Sierra Club v. Morton suit that skyrocketed Stone’s question and later article to fame, the 2005 case involving the Little Mahoning Creek in Pennsylvania, and most recently a Florida suit to protect Lake Mary Jane.

However, Indigenous Nations in the U.S. and globally have begun a struggle for the more encompassing, transformative legal idea often shorthanded the Rights of Nature. The Earth Law Center describes the idea as “a holistic worldview in which human beings and natural entities are interdependent and connected beings, [which] recognizes that Nature has a value in herself…[it] is promoting a shift in our collective consciousness of our relationship with Nature, and transforming the ethics, values and beliefs that underlie our legal, governance and economic systems.”

Indigenous tribes in Ecuador lead the way in 2008 when they instigated the first national movement to amend the constitution to include a recognition of the rights of nature. They succeeded. The new Ecuadorian constitution recognizes the rights of Pachamama (a term for Mother Earth used by the Indigenous peoples of the Andes) including the right “to exist and to maintain and regenerate its cycles, structure, functions and evolutionary processes” as well as the “precautionary rule” meant to protect natural resources even when it is not one hundred percent clear the impact on the environment.

This sweeping step has inspired other nations to follow suit. Panama legally recognized the rights of nature this year and Chile is currently redrafting its constitution including a new article for nature’s rights. In 2017, New Zealand, which relies on a common law legal system like the U.S., recognized personhood for the Whanganui River in a landmark move collaborating with Indigenous tribes to establish guardianship for the river.

In the U.S., Indigenous groups have largely worked within the national legal system but recently have embraced the Rights of Nature movement to enshrine in law their traditional Indigenous conceptions of the human-nature relationship. In Minnesota, the Ojibwe tribe is suing on behalf of the rights of Manoomin, a species of wild rice that is threatened by the Line 3 pipeline.

Inspired by the tribe’s efforts, in 2019 the Yurok Tribe in Northern California adopted a resolution recognizing the rights of the Klamath River. And in Seattle, the Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe is suing the city over its hydroelectric dams on behalf of salmon.

Nonetheless, while the struggle for a more comprehensive re-evaluation of the status of nature in the legal system is underway, the question of standing for natural beings remains a potential way to use the current legal system to better protect the environment where human voices fall short.

—-

In the year of the fiftieth anniversary of Stone’s seminal article, Common Home student editor Sadie Morris sat down with Georgetown Law professor Hope Babcock to talk about the impact, implications, and future of Stone’s question. The conversation soon also became one about the future of environmental litigation at large.

Common Home: Here we are fifty years from Stone’s 1972 article, Should Trees Have Standing? What are your initial thoughts about his piece at this point in time?

Hope Babcock: Despite its great promise, very little has happened with Stone’s article. It has not been cited often by law professors, let alone by courts. In spite of the excitement we all felt when it came out, nothing has happened. The question I am currently exploring in my new piece for the anniversary of Stone’s article is why has this line of thought stalled?

Common Home: It’s interesting to hear you so unequivocally say that little has happened with Stone’s piece in the U.S. even as the international Rights of Nature movement has picked up steam. What makes the U.S. different?

Hope Babcock: The idea that a tree could go to court and demonstrate it has been injured has been a nonstarter for a lot of folks. It seems to me that the barrier in the United States, for reasons that I am now exploring, is much higher than in other countries. So you find that yes, the idea has more viability outside of the United States, although it is not unchallenged.

The idea that a tree could go to court and demonstrate it has been injured has been a nonstarter for a lot of folks.

Prof. Hope Babcock

Common Home: Even though the current ethos in the U.S. regarding nature is likely to make a constitutionally enshrined version of the Rights of Nature impossible, you have suggested in the past that there are other extensions of rights to non-humans already in U.S. law that provide apt parallels. Can you elaborate on that?

Hope Babcock: Yes, in the U.S. we have given inanimate objects, namely corporations, rights. So I said, coming from an environmental perspective, well, of course, we’re so business-oriented that if corporations are trying to get into court and there is this obstacle of standing, the courts will quickly climb over it. But when it comes to animals or trees or whatever, they aren’t willing to do it, even though the door opens up the minute you say, non-humans can get rights. The concern had been the courts wouldn’t want to open the door at all, but they opened the door. But I think the courts fear that if it’s outside of that now sphere of injury, they will lose control and the courts will be swamped with cases. I say the same rules would apply to an animal as applies to a corporation.

The question is the capacity to stand up in court and whether the court will allow representatives of guardians to speak and they do, again, in the case of corporations. Why is it so hard to do on behalf of a noncommercial interest? A tree, a fish, a wolf, etc? Why can a corporation go to court? But a whale can’t go to court? Corporations can’t speak. Whales can’t speak. Corporations can’t think well, so they’re also dependent on a guardian.

As you alluded to, there are some countries that have given rights to nature in their constitutions. Would we ever do that? No. Why? Well, it gives too much power to nonbusiness interests. And, if I want to think as a proceduralist or a law professor, it gives an open invitation to all kinds of abuse, which means the courts are going to have to work really, really hard to keep a lot of stuff out of their chambers or out of their office, or their courtrooms.

It is interesting to compare the environmental situation to what happened during the civil rights movement because there was a sense that with the new civil rights legislation, every Dick, Harry, or Jane could bring a claim, suddenly, on an amorphous showing of discrimination. But somehow, we kept charging ahead on that one. In the environmental area, nobody’s charging. That’s what bothers me. Because obviously, there is a parallel between civil rights and the environment in terms of the resistance to them. It was a hard slog, you know. But even then, the civil rights litigation had the Constitution on their side–it just had to be fleshed out in court–but we do not have that in the environmental area.

Why can a corporation go to court? But a whale can’t go to court?

Prof. Hope Babcock

Common Home: You have written that an economic interest can be used to make the case for personhood; that is one of the factors supporting personhood for corporations. How is that challenging in environmental cases? How is that changing as more and more ways to put an economic value on the environment are developed?

Hope Babcock: It’s on my list of things to look at more deeply. I think that the world has not changed sufficiently to the point that an entity that doesn’t have an economic number attached to it can actually stand in court. Alternatively, you can say, I can put an economic value on the whale. So why is it any different from a ship? I keep coming back to, even though I don’t want to, the courts’ fear of environmental cases. They don’t want to get into an area of knowledge that the courts are unfamiliar with like scientific numbers. And there is the potential to be swamped.

You’d have to think of some way of having, I think, good standards for guardians. You shouldn’t be able to walk into court and say, “Well, I’m a friend of this whale, and therefore I want to file a suit.” It would require some greater showing. As a safeguard, as I say, the injuries would have to be capable of monetization. But even then, at some level, why do we have to know the worth of a whale in order to bring an injunction action to prevent something from happening to the whale–what difference does the value of the whale make? At the end of the day, there’s no reason a court cannot control the flow of requests.

Common Home: People thought the courts would receive far more environmental cases after major environmental legislation in the 1970s allowed for citizens’ suits on behalf of nature, but that didn’t happen. Why not?

Hope Babcock: Yeah, it’s interesting. Why aren’t the doors swinging open? I don’t know the answer. I mean, there’s a wonderful thing about being a law professor I discovered, as opposed to just a practicing lawyer: I don’t have to have the answers, I just have to ask good questions.

I haven’t brought a case for a while, but even in the 70s, you were still working overtime to persuade the court that yes, there was an injury, let alone get over the other jurisdictional barriers. And my sense is that these barriers are worse in the environmental area, maybe because of the scientific stuff, maybe because of lack of familiarity, maybe because of the commercial countervailing interest, I don’t know. But it’s harder to make an argument today on behalf of the environment than actually, it was a while ago, which seems so ridiculous given how far we’ve come. You can get really, really discouraged in this business because you think, okay, I know it’s a big rock, I’m trying to get up a steep grade, but if I keep my shoulder to it, eventually we’re going to make it. I don’t feel that way. I feel that not so much that the steep slope has gotten steeper, but that it has to do with the courts themselves. The courts simply do not want these cases, enough for them to stop them. Because they are time-consuming. They are difficult. They require the judge and their clerks to bury themselves in arcane, complex scientific stuff. If I were a judge, from an efficiency standpoint, I would ask is it worth it?

Common Home: Are there other reasons for this amount of pushback to environmental cases?

Hope Babcock: To some extent, it is the impact on industry that environmental cases threaten. Environmental litigants should pick their cases carefully because they want the impact to force companies to make changes in their practices. But, historically, very few cases have actually had that impact on companies. Most companies survive and are able to pay whatever fines they incur. But, there is still a threat of monetary impact on industry. There’s also the effect on the public. Prices may go up and may affect them as well. You can’t complain about an industry disposing of some horrible chemical if you know that the public is disposing of a variation of that same horrible chemical down their drain. So it’s really hard stuff. I’m glad I didn’t think these thoughts when I started out–I probably never would have done it.

Common Home: Some people claim that the courts are right to limit the environmental cases that they take because many of the questions coming before them belong in the realm of the legislature. What do you think?

Hope Babcock: If you’re looking to Congress for heroism, forget it. Sure, the president can issue an executive order but then a new president comes in and issues another executive order that counteracts the first one. So it’s really got to be a long-term change, and Congress is the only entity other than a court that can make a long-term change. So if the courts hang back saying, “Well, this really is more a matter for the legislative branch,” then nothing’s going to move. The barriers that Stone was speaking to in his 1972 article, are still there. If anything, they are deeper, wider, higher. So the fix, the idea of granting an entity, a nonhuman entity, the right to go to court, or the ability to go to court is still incredibly important. If anything, you might argue more important today than ever.

But, it’s a catch-22. You can’t bring the cases that would demonstrate the popular concern that might lead to legislative change. And even if you’re successful in filing a case, and get beyond the motion dismiss, you still have to frame it in a way that removes it from the rights of nature framework and into a quite standard realm of which the courts are comfortable. And that means you’re doing this forever. You can’t say I am speaking for the trees. Because they have no right to be in court.

Common Home: On top of all that, the cases you are most familiar with are in the footsteps of the major environmental legislation of the 1970s which focuses on pollutants, endangered species, etc. What about climate change litigation where the claims are often even more amorphous?

Hope Babcock: I have not been a fan of climate change litigation. I think it is extremely difficult to prosecute, and along the way, you lose a lot of ground. The only way you win is incremental. If you win on climate change, you win big. But if you don’t win on climate change, you have to be careful you don’t lose big. Litigants must know how to choose cases. One of the criteria for us was obviously the likelihood of success. Now you can also bring cases where the likelihood of success was lower but then the flip side of that was that the loss would not be that big. My sense is that there is less litigation today than before. Maybe that is because when I was litigating, the doors were wide open. What remains are really the hard, hard cases. They take a lot of time to bring and a lot of investment.

Common Home: Given everything we have talked about, what do you think about the future of environmental litigation? Are you hopeful?

Hope Babcock: I don’t think we ever really give up or else we wouldn’t be in this line of work. Hopeful? I’m really disappointed that things haven’t moved, especially given the physical evidence of human impact on the planet. I think many of us have been doing this for so long, seeing so many defeats, that many of us are paralyzed. Maybe what we need, is for the next generation to come in, who doesn’t know squat, and say “What the hell, let’s go for it. It’s bad. How much worse can we make it?”

Hope Babcock is an environmental and natural resources law professor at Georgetown University. From 1981-1991, she served as deputy general counsel to the National Audobon Society as well as their Director of Audubon’s Public Lands and Water Program from 1981-87. She was also a member of the Standing Committee on Environmental Law of the American Bar Association and served on the Clinton-Gore Transition Team. You can find her 2016 article on Stone’s 1972 article here. Her updated reflection in the Southern California Law Review is forthcoming.

Note: Minor edits have been made for clarity and concision.