High-Seas Fishery Managers Should Oppose Deep-Sea Mining

By Camber Vincent, SFS ’24

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is staring down a ticking time bomb to finalize regulations that will govern the exploitation of minerals obtained through deep-sea mining of the international seabed.

On July 9, 2021, a “two-year rule” was triggered by Nauru, a tiny island nation in Micronesia, giving the ISA just two years to finalize the rules and regulations for deep-sea mining. The ISA attempted to finalize regulations in July 2023 but were unable to come to a final agreement–the best they could do was an agreement to establish a regulatory framework by July 2025, buying two more years. If the ISA fails to meet this new benchmark, provisional licenses to begin mining will be granted with no regulation in place, setting off a race to mine the ocean floor.

Previous meetings of the ISA, including those in March 2023 and July 2023 have yielded little progress toward finding consensus on the regulatory framework. It remains unclear whether and when the ISA will permit mining to begin.

Many member states of the ISA expressed concerns with deep-sea mining, feeling unsettled by a lack of knowledge regarding the impacts of the process on marine life and ecosystems.

We know deep-sea mining will have a number of impacts on the marine ecosystem, including noise pollution, the removal of ambient water, the destruction of sea-floor substrate, the alteration of habitat and sediment plumes. Sediment plumes are not well understood, but from small-scale field experiments, have been found to potentially smother organisms, release toxins, acidify the water, deplete oxygen and disperse pathogenic material, while also increasing turbidity — the clarity of water — which can affect water chemistry and microbiology.

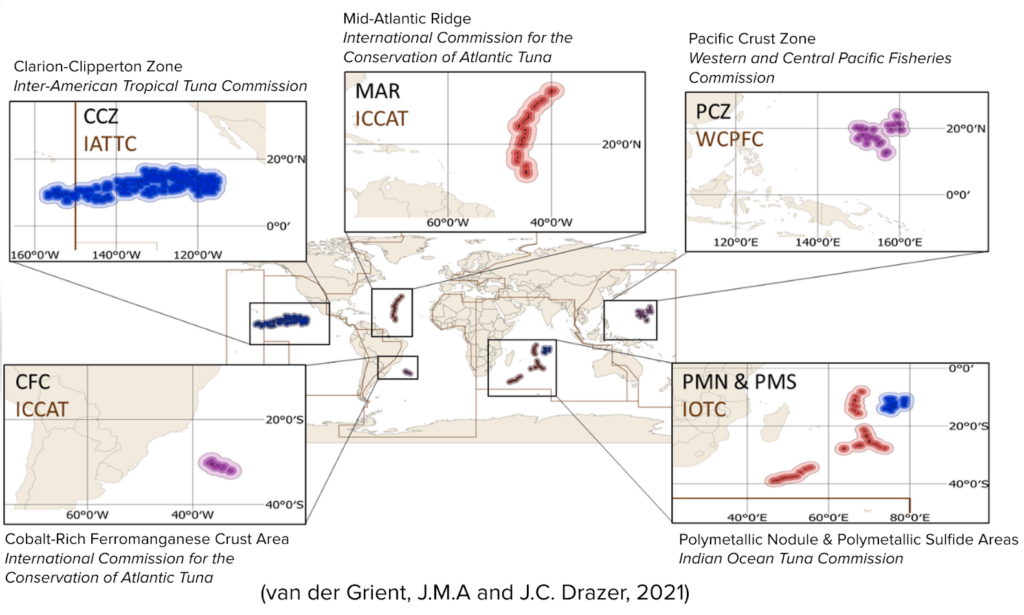

Modified map of global high seas mining areas. Image courtesy of J.M.A van der Grient , J.C. Drazen, and Camber Vincent.

We don’t know just how drastic these impacts will be, how far away from mining sites they will be felt and how long it will take for marine ecosystems to return to equilibrium should deep-sea mining be permitted.

One such high-seas study published in “Marine Policy” in late July 2021 displayed an overlap between high-seas fisheries and deep-sea mining zones. Previously considered unrelated industries, the article led the charge to bring high-seas fishery managers into the conversation on deep-sea mining.

The study found that the five zones of which interest for deep-sea mining exploitation is highest overlapped with high-seas fishing grounds managed by regional fishery management organizations (RFMOs). Furthermore, the study estimated that there would be impacts on fisheries regardless if plumes only disrupted 50 kilometers (km) around the site (as is in order with lower estimates) or up to 200 km around the site (in accordance with higher estimates).

At 200 km, deep-sea mining operations would overlap with a region outputting roughly 80,000 tons of annual catch in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. The operations would overlap with an additional 70,000 tons of catch across four other primary fishing regions. Regardless of exact quantification, the study clearly demonstrates that fishery stakeholders should be aware of spatial overlap with deep-sea mining operations and must contribute to conversations on mining regulations as a stakeholder in the blue economy.

The spatial overlap of the two operations will interfere with fisheries’ abilities to pull in healthy stock for sale on the market. Competing technological equipment may affect each’s operations, and fish stock living patterns may rapidly shift in response to mining operations.

More importantly, mining operations could increase concentrations of toxic metals in the water column, killing marine life directly or remaining present in fatty tissues through bioaccumulation. This accumulation of toxic metals can then biomagnify up the food chain, and the final catch destined for the market is delivered to consumers with heavy doses of toxic metals.

Beyond the direct impacts of mining operations, high-seas fishery managers must be aware of the indirect impacts of deep-sea mining on marine species. Marine ecosystems already face immense stress from a combination of factors, including “climate change, acidification, deoxygenation, pollution and over-exploitation of living marine resources,” and another stressor — mining operations — may cause an ecosystem crash.

In addition, mining locations often coincide with important ecosystems, like seamounts, which provide vital habitats for marine species to feed, breed and nurse their young. When disrupted, these ecosystems may never recover on a human time scale.

Furthermore, midwater ecosystems have been heeded little attention, with the focus dedicated to mining impacts on seafloor environments. These midwater ecosystems represent a huge amount of the marine biosphere and play key roles in carbon export, nutrient regeneration and provisioning of healthy fish stocks — all of which are at threat from deep-sea mining impacts. The turbidity and noise impacts from a single mining site can travel hundreds of kilometers, with known negative impacts on organisms’ behavior, physiology and survival rates.

High-seas fishery managers are uniquely positioned industry stakeholders with significant connections to other actors in the marine regulation sphere, and they have an opportunity to leverage their strong networks in opposition to deep-sea mining.

Given the widely understudied and unknown interconnections of high-seas ecosystems, we cannot provide an accurate model or estimate of how deep-sea mining will devastate marine ecosystems, but we know it has the potential to. High-seas fishery managers must urge for the application of the precautionary principle — calling for caution, pausing, and review before implementing a new technology — in approaching the debate on allowing for deep-sea mining operations to commence. High-seas fishery managers are uniquely positioned industry stakeholders with significant connections to other actors in the marine regulation sphere, and they have an opportunity to leverage their strong networks in opposition to deep-sea mining.

Of course, we must also recognize that high-seas fisheries are not a beneficial industry to marine ecosystems. High-seas fishing is often listed as a primary threat to sea life due to stock overexploitation, damages from bycatch, noise pollution, interference in open ocean and deep-sea ecosystems and environmental degradation. High-seas fishing would also largely be unprofitable without the government subsidies currently offered. Nonetheless, high-seas fishing continues due to the outsized influence industry leaders have in governance decision-making. If they already have the influence, why not put it to good use?

Deep-sea mining is likely to be far more invasive and damaging than high-seas fishing, and we know a lot more about fishing and its impacts than we do about deep-sea mining. Bringing high-seas fishery managers into a diverse coalition of actors opposed to deep-sea mining will likely bolster the chances of regulatory success and could also form an unlikely partnership for cooperation on other threats to the high-seas like those from high-seas fishing.

As the ISA Council and Assembly prepares to reconvene for their next sessions from July 10 to 28 — when the two-year time bomb goes off — officials must be urged and prepared to consider the legal option to adopt a precautionary pause or moratorium on deep-sea mining. Once deep-sea mining begins, it is unlikely to stop, and once marine ecosystems are disrupted, they will be impossible to restore. Given the dire, ecosystemic threat from deep-sea mining and the rapidly closing window for opposition to form, high-seas fishery managers must wholeheartedly oppose deep-sea mining and work to see the imposition of a moratorium in due time.