Revisited: Shelby Gresch, the Force Behind the Hoya Harvest Garden

For our one-year anniversary issue, this piece is part of a series revisiting past contributors to Common Home. In Issue 5, Shelby Gresch (SFS ’22) wrote about her work at the Hoya Harvest Garden, Georgetown’s new community garden. In this piece, Common Home Editor Madhura Shembekar (SFS ’26) and Gresch revisit her work at Georgetown..

Shelby Gresch graduated from the Walsh School of Foreign Service with a degree in Science, Technology and International Affairs. She is currently a post-baccalaureate Fellow at the Earth Commons.

For online version: You can find Shelby’s past contributions here.

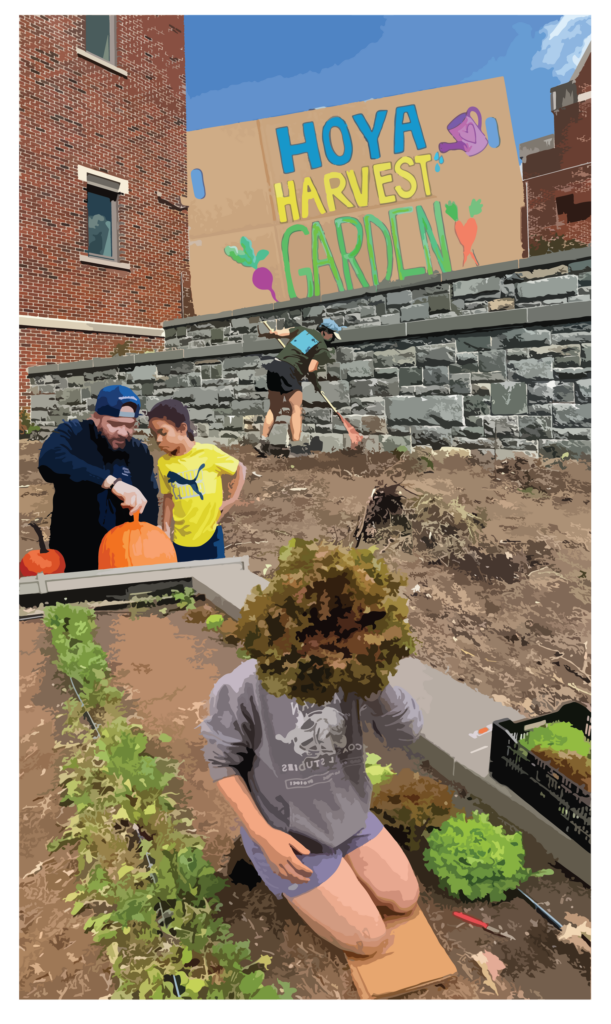

Photo collage of people collecting vegetables, raking, and carving pumpkins. Photos provided by The Earth Commons; Design by Cecilia Cassidy.

MS: You do incredible work as a post-baccalaureate fellow at the Earth Commons and the manager of the Hoya Harvest Garden, Georgetown’s new community garden. What has been your journey with the Earth Commons both as a student and now as a graduate of Georgetown?

SG: I first connected with the Earth Commons through a Biology of Migratory Animals class taught by Dean [Peter] Marra during my junior year. I’m passionate about food justice and sustainable agriculture, so I knew I wanted to get involved with the Earth Commons when Dr. Marra casually mentioned starting an educational garden on campus. I applied to intern during my senior year and was given the opportunity to lay the groundwork for making that garden a reality.

I spent my senior year visiting urban farms throughout the city and on other college campuses to learn best practices from folks already doing the work as well as gathering input from the Georgetown community about what they’d like to see from a project like this. That was a particularly fun part of the process because people were super enthusiastic and had a million ideas — everything from very specific crop requests to ideas for outdoor classroom space to canning workshops and more. The biggest takeaway was simply that people were jazzed about the idea of more gardening space on campus and wanted it to meet a variety of community needs, primarily increased access to fresh food for those experiencing food insecurity. When graduation rolled around in the spring, we had a detailed proposal, but were still waiting to hear where, if anywhere, we would be able to pilot the project on campus. I really wanted to see the project through, so I applied to stay on as a Post-Bacc Fellow.

When I officially started the fellowship in the fall of 2022, I received the news that the garden was a go and that we would get to use the mid-campus terrace as our pilot location. So, for the past year and a half, I’ve been focused on getting the garden up and running and putting systems in place for it to thrive for years to come. It’s been such an incredible experience to get to lead this project and work with folks across the university, and I am so proud of what we’ve been able to accomplish. This experience has also really solidified my commitment to sustainable agriculture, and I have learned so much about what that entails in practice. My favorite part, though, has simply been the daily joy of connecting with people in the garden. Everyone eats, so everyone should care about and understand how food is grown and what broader impact that may have. Beyond that, food is closely linked to community and culture, and I’ve been lucky to experience that firsthand as folks share their stories (and occasionally seeds) from different plants, places and people with me when passing through the garden. This sharing feels like what we are supposed to do — a natural response to bounty.

MS: The Hoya Harvest Garden is sometimes referred to as a “Living Lab” — a campus-based open ecosystem that involves hands-on sustainability research run by students, the university and others. How has working at a Living Lab impacted, spurred or altered your interest in sustainability and biodiversity?

SG: I’ve always been deeply interested in caring for the environment, but working in this context specifically has opened my eyes to urban biodiversity and biodiversity in food production spaces. The thing that inspires me about the “Living Lab” model is that we can use our campus as a test-bed for sustainability practices that can be applied elsewhere and at a larger scale. For example, the Hoya Harvest Garden relies on a variety of sustainable agriculture practices that promote biodiversity for both pest management and nutrient cycling. These same practices can be used by farmers on a larger scale, and they can also be deployed in non-food-producing landscapes to create habitat for wildlife (including insects). Using a campus landscape this way and measuring the outcomes allows us to imagine stewarding other landscapes like this as well. Imagine if we grew food and flowers everywhere we currently have ornamental landscapes in the city!

MS: The Hoya Harvest Garden uses some Indigenous agricultural practices. How did you decide that you wanted to employ them, and have they been successful? What’s the importance of culturally diverse agricultural practices?

SG: We employ some Indigenous agricultural practices, namely the Three Sisters and other forms of “companion planting” because they came up several times in our initial interviews with GU community members, and because they are just best practices in “sustainable agriculture.” The Three Sisters is practiced by multiple Indigenous peoples throughout North and South America and involves the planting of corn (or maize), beans and squash together in one plot where they can cooperate instead of competing. The “sisters” work together because the corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb; the squash sprawls out and suppresses weeds; and the bean fixes nitrogen that becomes available to all three. The Three Sisters bed in the garden this year was highly productive per square foot and teeming with life. However, we are certainly still learning this practice and will likely use different corn, bean and squash varieties next year because our timing was a bit off — the corn ripened faster than expected, so it was toppled by the beans and many of the squash didn’t mature before the first freeze.

Culturally diverse agricultural methods are essential to creating a welcoming space for everyone in the garden, but also because Western industrial agriculture — while highly productive — is a major contributor to the very environmental problems that we are trying to solve. Our current food system, which relies predominantly on “conventional” or “industrial” agriculture, accounts for more than a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions and is a main culprit implicated in mass biodiversity loss due to habitat destruction and pesticide use. As is the case with many strategies for mitigating climate change and environmental degradation, much of what is today being touted as new “regenerative” or “sustainable” methods that will save our food system originate in Indigenous knowledge and an understanding of farming with nature instead of subjecting it. For example, cover cropping — the practice of planting non-commodity crops under, between or after commodity crops — builds soil health; helps with water infiltration and pest management; and suppresses weeds. This runs directly counter to conventional farming methods, which rely on herbicides to keep fields free of all but the desired crops, and instead, more closely mirrors natural systems where bare ground is the exception, not the rule.

I think it’s critically important to recognize and showcase these more cooperative approaches to farming and landscape management in the Hoya Harvest Garden, and I hope that it will spur further conversations about how we can employ such methods to save our planet without co-opting them. I think it’s important to recognize that there is a very real tension when Western countries and companies use these strategies (and often profit from them) to mitigate climate change and increase food security when the history of the Western food system is also inextricably linked with Indigenous genocide, displacement and slavery. I’m not sure how exactly to address that tension, but I do think that farming necessarily opens the door to thinking about how we heal the land and our relationships with it.

MS: In the future, do you hope to work more on sustainable agriculture, or is there another area of sustainability or environmentalism you’d like to explore?

SG: I am definitely hoping to continue to work in sustainable agriculture! I’ve learned a lot about community engagement, project management and, of course, gardening from this role, but I’ve also just been rejuvenated by getting to enact change in real-time. I’ve been passionate about environmental issues for my whole life, and as anyone who works in this field knows, the pace of change can be frustrating and exhausting at times. This role has taught me that one of the best antidotes to ecological grief and burnout is simply hard work in nature — it’s given me so much hope and joy to physically care for a little corner of the planet. I hope to continue to harness that feeling in whatever part of sustainable agriculture I work in next — be it policy, farming, research or something else. There is still a ton of work to be done in making our food system more sustainable, resilient and just, and I am excited to play a little part in it.