Urban Farms: A Chicago Suburb’s Proposal for Change

By Chloe Hammock, SOH ’25

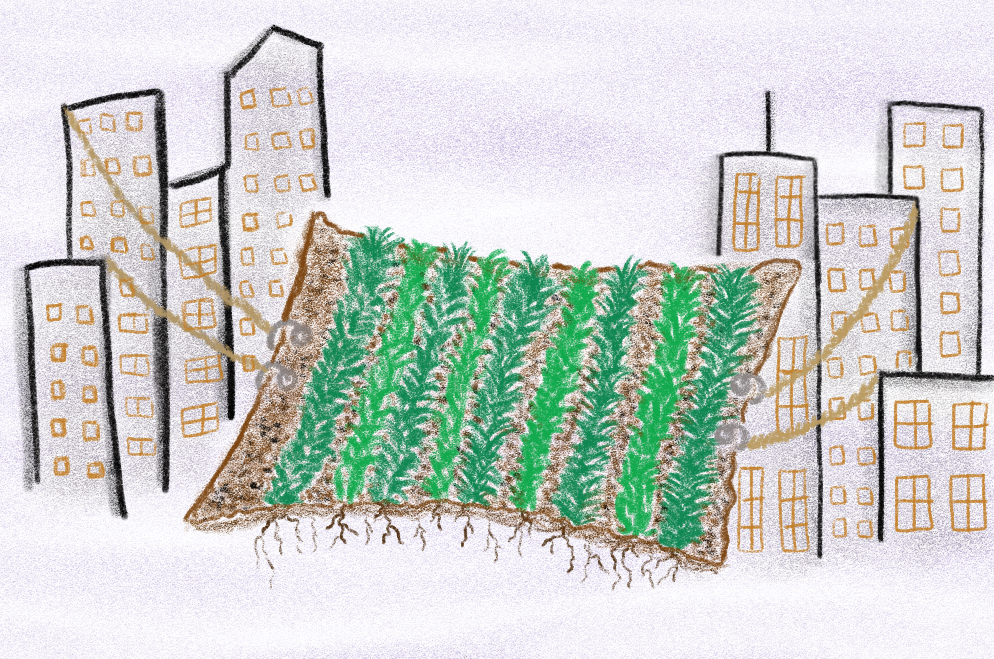

Drawing of a garden hanging between two sides of a city. Design by Cecilia Cassidy.

Evanston, Illinois — the first city north of Chicago — is where I call home. Last September, residents of Evanston cast ballots to decide how $3 million from the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) would be invested in the community. Amongst other projects, residents voted for the creation of an urban farm. This one-acre urban farm sets out to sustainably grow local fruits and vegetables for the community.

The Evanston Urban Farm is managed primarily by Evanston Grows, a local non-profit collective aiming to reduce food insecurity and build community in Evanston. The proposal notes that “the healthy, nutritious food grown here can be distributed free or at a low cost to food-insecure households and communities and eventually can become self-funding.” The project’s flyer draws attention to the 24.6% increase in food insecurity in Cook County (which encompasses the greater Chicagoland area.) Moreover, as food prices have increased by over 11%, COVID-19 SNAP benefits have ended.

Originally, community gardens were created across the United States as a way for low-income and marginalized groups to economically grow fresh produce for themselves, reclaim and beautify public space in their neighborhoods and push back against the narrative of individualistic claims to property. Today, however, community gardens are caught within the web of the Alternative Food Movements. They are considered “trendy” by many white affluent renters seeking to live out their sustainable values.

The trend toward wanting sustainable, local food systems does not operate in isolation. Scholarship has shown that racialized gentrification is often accompanied by increases in urban agriculture. While urban gardens have positive benefits for their community, they are also being co-opted from a form of resistance to an often “colorblind” white aesthetic that fuels gentrification.

In a city like Evanston where already over 30% of residents are at risk of being priced out of their homes, will this city-driven initiative only further the displacement taking place?

In the Sustainability Myth: Environmental Gentrification and the Politics of Justice, Melissa Checker identifies displacement across neighborhoods in New York — from the Lower East Side to Brooklyn — related to “green” gentrification, including the establishment of community gardens. She argues that “the meaning of urban community gardening changed from a grassroots movement that contested the state, to represent ethnic identity, to secular culture, and finally to sustainability ideals of urban food production.”

The creation of a city-funded urban farm in Chicago would entirely distill and distort the core origins of community gardens that were once rooted in self-sufficiency and resistance to the state. While I think the garden will provide educational experiences for the community and can meet the needs of some residents, the question remains: Are there better ways the city could be spending its money? It is imperative that the city explicitly delineates the contours of food insecurity in our community and considers in depth whether an urban farm is an appropriate solution.

The creation of a city-funded urban farm in Chicago would entirely distill and distort the core origins of community gardens that were once rooted in self-sufficiency and resistance to the state.

Last summer, a report was published by the Evanston Health Department mapping many health indicators across census tracts in the city. The results are unacceptable, yet perhaps, unsurprising. One of the historically redlined wards in Evanston, the 5th ward, has compounding factors influencing its access to healthy foods, income levels, life expectancy and more. When you also look at the map comparing the concentration of white residents, the evidence of environmental and structural racism becomes even clearer.

We will have to wait and see where Evanston’s urban farm is located. If it’s placed closest to those who need it most — without any other policy considerations by the city — it risks accelerating the gentrification of the neighborhood and increasing the risk of displacement. However, if it’s placed further from those who need it most, its accessibility is reduced.

Although an urban farm may provide some helpful assistance, it is a band-aid solution. Food justice scholar Julie Guthman writes in, “Bringing Good Food to Others” about how some of the communities she partners with echo the desire simply for a Safeway in their neighborhood over white-imposed organic produce.

While we may not have any Safeways in the Midwest, maybe part of what Evanston really needs is the Chicagoland alternative, a Jewel-Osco.