A Single Seedling

By Eliana Mlawski, CAS ’26

This is one of two student selections from the Georgetown undergraduate course, Environment and Society, a foundational, survey course in the Environmental Studies program, covering theories and applications in science, policy and humanities. The course is taught by Professor Randall Amster and Professor Rebecca Helm.

In the United States, approximately 40% of all food goes to waste every year. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) determined that the amount of uneaten food contains enough energy to power 50 million homes for a year, yet it accounts for an astounding 24% of all landfilled materials.

Loss occurs at each step of the supply chain and directly contributes to a range of issues including natural resource exploitation, pollution, food insecurity, environmental racism, and climate change. Although 34 million Americans experience hunger, more than 73 million metric tons of food are unharvested or underutilized annually.

For my Community Engagement Project in the Environment & Society course at Georgetown, I decided to focus on the intersection between food security and environmental justice in Washington, D.C., after learning about high obesity rates throughout predominantly Black, low-income neighborhoods of Ward 8.

While working as a Development Intern at the New Hampshire Food Bank during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, I had the opportunity to learn from single moms and grandparents working tirelessly to make ends meet. I saw how hunger is as pervasive as it is corrosive, especially for historically marginalized groups.

Although Georgetown is reportedly wealthier than 96.9% of all neighborhoods in the U.S., our campus still feels the effects of systemic poverty. Anyone could unexpectedly find themselves in an impossible situation, regardless of their family background or education level, and our neighbors should never have to choose between feeding their kids or paying the rent.

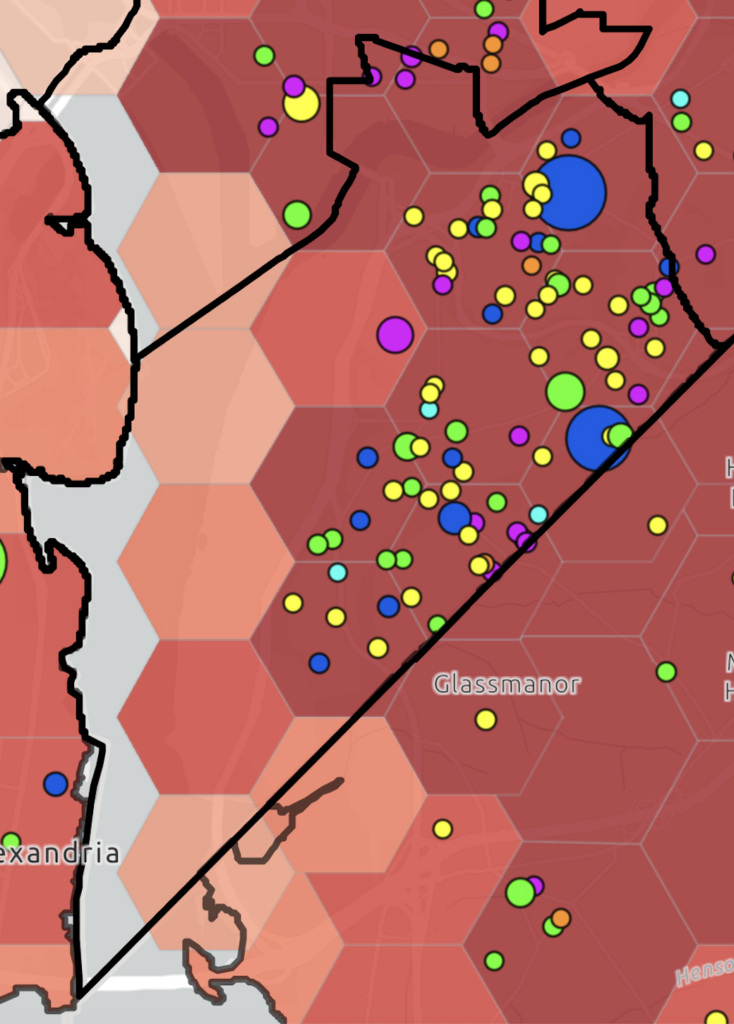

Image of Ward 8 from The Hunger Heat map. The redness of the neighborhoods represents the number of food insecure households there are, with the lightest color representing 0-9 and the reddest area representing more than 5,006 as of 2023. Image courtesy of Capital Area Food Bank.

After joining the Georgetown Renewable Energy and Environmental Network (GREEN) and researching Georgetown’s waste management infrastructure, I realized that I was ready to take action. As an underclassmen surrounded by so many accomplished experts, I initially doubted my ability to speak on food waste issues and make a difference; however, my coursework pushed me to try because even small actions can have a great impact.

One of our central texts, “All We Can Save,” doesn’t intend to reinvent the wheel. Instead, many essayists urge readers to return to their roots. Xiye Bastida, an Otomi indigenous climate activist from Mexico, explains that a “regenerative future is possible — not when thousands of people do climate justice activism perfectly but when millions of people do the best they can.” Throughout the fall semester, I dedicated more time to reflect upon my positionality and priorities through this lens. I realized that I am personally and professionally passionate about environmental justice, so I should consider a wide range of new opportunities to explore this career path. Furthermore, I learned to take initiative because I already possess the problem-solving, community organizing, and research skills necessary to get started.

Narratives have power, and I believe that my story is about building bridges.

While growing up in the woods of rural New Hampshire, I learned to value environmental stewardship which connects my community to our land. Only recently, after moving to Georgetown for college last year, did I recognize how much nature also contributes to my well-being.

As a first-year student, I was startled by my acute longing for the ancient, unmanicured trees that I was accustomed to taking for granted at home. Nature provides so many tangible ecosystem services, yet it’s often difficult to quantify the spiritual and cultural benefits I gain from sitting beneath the forest canopy. As our class discussed, ecosystem valuation can be a useful practice to justify conservation to political and business decision-makers, but it often fails to recognize the intrinsic worth of a healthy ecosystem. After studying these issues in class and attending more GREEN meetings, I launched into action to mobilize with my peers.

Throughout this challenging process, I was excited to find a supportive community of environmentally-conscious students who care deeply about food justice. Coordinating with my friends on the GREEN and Food Recovery Network boards, I planned an educational workshop about Congress’s role in re-negotiating the Farm Bill and a sustainable farm volunteer trip.

In preparation for the GREEN workshop, I created a food justice flier to post around campus, a presentation slideshow, and linktree of additional resources. During this event, I hoped to provide a foundational understanding of general issues like food insecurity, waste, and sustainable agriculture. I focused on themes from Dr. Robert Bullard’s environmental justice research and Soul Fire Farm’s approach which centers food sovereignty to empower people of color in upstate New York. For example, I explained Bullard’s finding that environmental racism systematically harms poor, Black, and working-class individuals as a way to illustrate why food apartheid has such an extreme effect on Wards 7 and 8 of D.C. To tackle these complex challenges, I employed Bastida’s strategy of starting small. Rather than attempting to teach an entire food justice crash course, I covered specific topics like food waste, the Farm Bill, and ways to get involved with D.C. hunger alleviation organizations.

Flier encouraging others to think about what food justice means and looks like. Design by El Mlakski

Next, I researched local hunger nonprofits and decided that JK Community Farm would be the perfect partner. The small nonprofit has a small yet mighty team of only three employees, so they rely upon thousands of volunteers to manage 150 acres of land in northern Virginia. JK Community Farm is committed to donating 100% of its produce to distributors like D.C. Central Kitchen, aiming to “provide food education and alleviate food insecurity with nutrient-dense produce and protein.” When discussing the potential event with Samantha Kuhn, the Executive Director of JK Community Farm, I was amazed by her absolute dedication to their mission. She proudly described JK Community Farm’s commitment to regenerative agriculture, as the farm implements only sustainable, chemical-free techniques such as nutrient testing, crop rotation, and cover cropping.

By the time I was ready to lead the GREEN food justice workshop in early November, I thought I knew what to expect. I had experience facilitating dozens of similar discussions in high school, but I did not expect the 22 GREEN attendees to be so engaged. During those 30 minutes, they didn’t hesitate to ask questions. We ultimately ran out of time while discussing the Capital Area Food Bank’s hunger map of D.C.. Moreover, participants brought up great points about efforts on campus like the Hoya Hub and Students Advancing Food Equity (SAFE). I especially enjoyed the Food Recovery Network Co-Presidents’ contributions, as they spoke about their first-hand experiences lobbying Congress for a stronger Farm Bill this past summer. I left feeling energized and optimistic about the future of food justice.

One week later, a handful of GREEN members and I ventured 52 miles northwest of campus to JK Community Farm in Purcellville, Virginia. When we finally arrived after an early morning commute, we immediately got to work planting lettuce and collard greens in two high tunnel greenhouses to prepare for the winter. In just one hour, we helped plant thousands of seedlings, which would grow into fresh salad greens for people experiencing hunger. The volunteer experience was incredibly rewarding and we had the chance to chat with new friends while enjoying the outdoors.

Later that morning, we helped pick up irrigation lines from the fields and harvested dozens of radishes. By the end of the afternoon, everyone was tired but satisfied because our efforts would directly impact the community. We ended the day with a tour of the farm’s expansive property including cattle pastures, raised plant beds, and beehives as Kuhn answered our questions. By the time we left, I felt inspired. We had gained some sustainable agriculture experience, learned more about local hunger issues and were looking forward to returning in the spring.

As I reflect upon these experiences, I’m grateful for all the friends who went above and beyond to make my final project possible. Effective collective action relies upon relationships. I didn’t have an official leadership title or polished plan, but people gave my passion project power. The GREEN workshop and volunteer trip both exceeded my expectations; our momentum is part of a greater environmental justice movement. Sustainable agricultural has proven itself to be a way in which to bring people together and fight hunger.