Mapping the Mysteries of Bird Migration

Author: Rowlie Flores

Every spring, as Hoyas prepare for final exams, billions of birds and hundreds of species migrate overhead, often northward from the tropics to enjoy the mild climates.

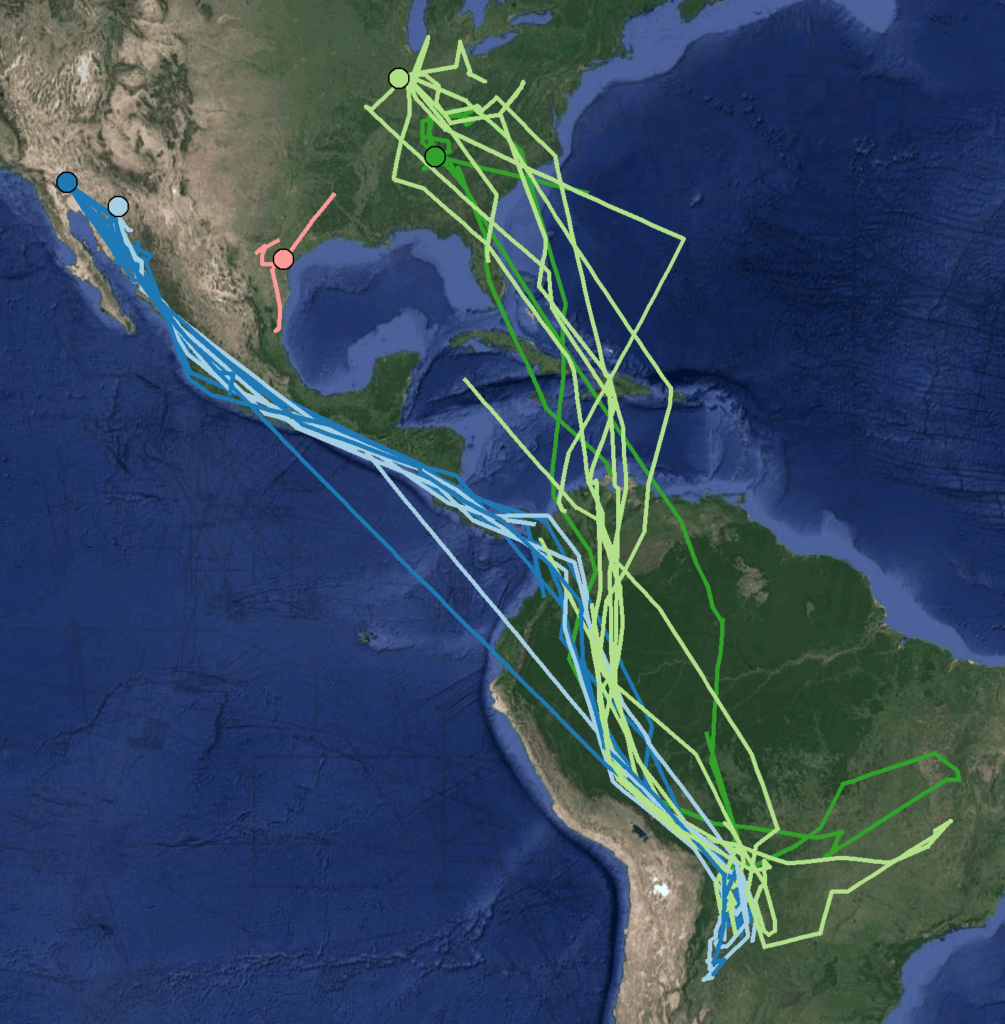

Georgetown ornithologists Dr. Calandra Stanley and Dr. Peter Marra are tracking the movement of yellow-billed cuckoos using Argos satellite tags, one of the only tags small enough to be used for studying birds.

Among their discoveries: these migratory birds are far-ranging athletes, much less sedentary than previously thought. Even within their own breeding grounds, the cuckoos often travel hundreds of kilometers.

The traditional view of a bird’s migratory journey, which assumed stillness during its winter and breeding months, runs counter to this reality. The yellow-billed cuckoos’ population has also recently declined, and conservation scientists struggled to figure out why.

In an unpublished tracking study, Stanley and Marra found that the cuckoos gathered in the Gran Chaco forest in South America, which was being rapidly destroyed by the expansion of agribusiness practices.

Uncovering the mysteries of bird migration is a career-long calling for both researchers. Dr. Marra has authored numerous books and papers on bird conservation and is, outside of his Georgetown focus, an Emeritus Senior Scientist at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center. Dr. Stanley is a post-doctoral researcher specializing in migration ecology and animal behavior at Georgetown’s Department of Biology and the Peter P. Marra Ecology and Conservation Laboratory.

And it has taken such dedication to manage the project’s “technical nightmares” as the yellow-billed cuckoos traverse the globe. According to Marra, “one of the study’s biggest challenges is that the birds are pretty small and the spatial areas they go are really large, like the entire area of Western Hemisphere.”

He added that the technology available to track smaller animals—such as birds—needs improvement. The Argos GPS tags have a solar panel on the back, so the individual behaviors of the cuckoos could affect their findings if the tags are not regularly charged by the sun.

Fortunately, the International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space (ICARUS) project may finally enable ecologists to accurately track both the precise movement patterns of animals during these migrations, as well as the locations of where they rest, feed, or die.

Although Dr. Stanley and Dr. Marra did not use ICARUS for their research, they believe that such improved global wildlife tracking systems could reveal revolutionary findings with more efficiency and ease.

Unlike traditional tracking methods that require researchers to accompany animals into their habitats, the ICARUS project tracks ecological movement from a new antenna on the International Space Station. It then sends geographic, environmental, and health data from tagged animals to a ground station in Russia. The project is an international collaboration hosted at the Max Planck Institute of Animal Behavior.

Instead of simply pinpointing where animals travel, the project can also tell how animals interact with their surrounding environments. Such insights can help researchers predict how animals are adapting to climate changes as well as how habitat fragmentation affects their migration patterns.

Since its attachment to the International Space Station in 2018, researchers have begun to attach large ICARUS tags to animals such as rhinoceroses, giraffes, and zebras. In the fall of 2020, they also began attaching smaller tags to species like blackbirds. As researchers attempt to improve tracking technology, they hope to create even smaller tags to track bats and insects as early as 2025, which would revolutionize the way that scientists address biodiversity loss.

One of the study’s biggest challenges is that the birds are pretty small and the spatial areas they go are really large — like area of the Western Hemisphere

Dr. Peter Marra

Dr. Stanley said that “the ICARUS tags are substantially cheaper than the other tags that are on the market currently,” including the Argos satellite tags that she and Marra used. While the technology isn’t quite there yet to be used on yellow-billed cuckoos, Stanley is confident that the ICARUS technology is improving and that smaller versions of these tags are plausible.

In addition to the cost savings, Stanley said the new ICARUS technology will provide researchers data on wildlife with more accuracy and less interference from environmental factors. ICARUS will not only track animals’ locations, but also their temperature and speed. As a result, the new technology will revolutionize wildlife tracking because it yields a holistic picture of animal behavior.

Further explorations of their work have been featured by The New York Times in “How Far Does Wildlife Roam? Ask the ‘Internet of Animals,’” and Science Magazine in “Terrestrial Animal Tracking as an Eye on Life and Planet.”