When Climate Displaces a Way of Life: The Uncounted Toll on Mental Health on the Front Lines of Climate Change

By Ben Oestericher, SFS ’25, Shabab Wahid, Edna N. Bosire and Emily Mendenhall

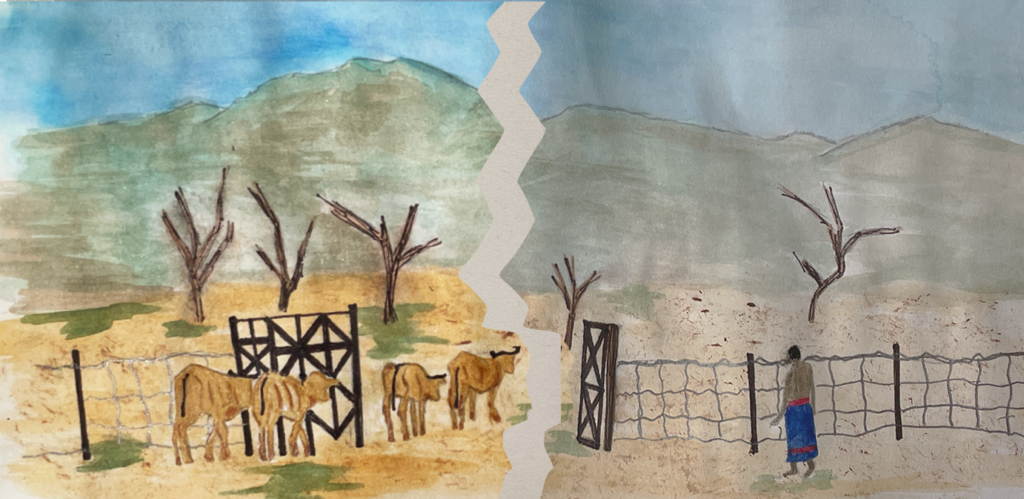

Watercolor of cows walking through a fence with a man towards a fading landscape. Graphic by Cecilia Cassidy.

In a port-side county of southeastern Kenya lies Kilifi. In Kilifi, more than half of the community depends on low-input rain-fed agriculture for the majority of their household income. Animal keeping, particularly of cows and goats, plays a vital role in the economy and shapes people’s conception of success and well-being. “Pastoralists derive their identity from having cows,” a local doctor said. “When these cows die prematurely, they don’t feel right as they are breaking a generational tradition and don’t know any alternative sources of livelihood-making.” In the past four years, Kilifi has experienced unprecedented drought conditions precipitated by climate change, causing animal deaths and crop failures that have affected more than 200,000 people in the last year.

This summer, we completed a two-month exploratory study of climate change and mental health in Kilifi County, Kenya, in collaboration with our colleagues at the Brain and Mind Institute at Aga Khan University in Nairobi, Kenya. Our trip was in conjunction with Professors Mendenhall, Wahid, and Bosire’s research on ecological grief, which describes the psychological response connected to the destruction of the environment. We interviewed 50 stakeholders across the county, ranging from policymakers and doctors to public health officers and community members. Through our conversations, we found that people were concerned about climate as an immediate issue as opposed to an existential issue. The common fear — from policymakers to modest farmers — was losing their way of life, source of livelihood, identity and traditions.

In Kilifi, well-being is conceptualized as the ability to provide for one’s family, carry on multigenerational cultural traditions, and live off of the land and local resources. Indeed, since the 16th century, the Mijikenda people, who make up a majority of residents of Kilifi County, have been engaged in horticulture and pastoralism in the area. Kilifi’s local values mirror those of the global recommendations for mitigating climate change: Look local, invest and grow what you have and build communities that can rely on each other.

Climate change in Kilifi is disrupting not only people’s physical health and livelihood but also their social and emotional health, preventing them from carrying on generations-old traditions that are core to their identity. “If I don’t farm, I am unable to achieve my life,” a medical doctor in North Kilifi told us. Other respondents noted that men, in particular, feel shame if they lose their ability to be breadwinners in their families. “They feel their family is not complete if they can no longer provide for it,” the doctor told us.

Interviewees described that women, on the other hand, who are traditionally seen as the family’s primary caretaker, face increased pressure as food dries up. “When a woman wakes up and can’t feed her child, she is mentally disturbed,” a nurse in the Rabai sub-county described. While international agencies and the domestic government have mobilized food aid in response to the drought, people in the county said that such aid could never repair the loss of dignity of not being able to make a living. “Food will never be enough when it is provided by someone else,” a public health officer said.

We heard dozens of stories about those whose mental health was negatively affected by the social impacts of climate change. “There was an older man I knew who was a happy and social individual. His source of joy was his fifty cows, [which] he used to care for his extended family,” a public health officer from Kilifi County said, “During the drought one year ago, all fifty of his cows died. The individual could no longer raise money to pay for his children’s school fees and became dependent on the government to provide. He ended up dying by suicide. He would rather lose his life than his way of life.”

This story illustrates the extraordinary impact of climate change on people who contributed very little to climate change in the first place. Not unlike farmer suicides linked to losing their lands because of debt, such as in India and the United States, climate suicides cannot be underestimated as a growing concern for mental health. However, the more subtle changes in generalized anxiety and moderate depression often remain less visible in the community and often uncounted. Thinking about how some of the most vulnerable to climate change experience these changes today and every day, and what those will look like in the future, is an urgent endeavor.

Ben Oestericher is a junior in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University. This research was supported by the Social Innovation and Public Service Fund and the School of Foreign Service Dean’s Fund.

Shabab Wahid is a public health researcher and assistant professor in the School of Health at Georgetown University

Edna N Bosire is a medical anthropologist and assistant professor in the Brain and Mind Institute and the Department of Population Health at Aga Khan University

Emily Mendenhall is a medical anthropologist and professor in the School of Foreign Service at Georgetown University