Challenges in Mangrove Restoration: Does it Work?

By Adam Shaham, SFS ’22 & Fulbright recipient

Adam Shaham graduated from the School of Foreign Service (SFS) with a degree in International Culture and Politics in 2022. He spent the last year in Mumbai, India, studying mangrove restoration through a Fulbright grant.

Image of Adam sitting on a raft in a river surrounded by mangroves. Photo courtesy of Adam Shaham.

Mangrove trees are critical to the world’s fight against climate change and ocean degradation. Nowhere is this clearer than in Mumbai, India’s second-largest metropolis. The city, composed of seven islands, was once covered in mangrove forests. Now, the remaining 65 square kilometers of mangroves left in Mumbai are under grave threat.

From 1991 to 2001, Mumbai lost 40% of its mangrove cover. Over the last 15 years, hundreds of thousands of mangrove trees have been cut down for coastal infrastructure development. The ongoing construction of the Mumbai Coastal Road is expected to further erode the city’s mangrove coverage by an additional 1%. Despite Mumbai’s considerable investment in restoring mangrove forests, there remains a glaring absence of comprehensive public evaluation to assess the efficacy and outcomes of rehabilitation efforts.

Through the support of a Fulbright grant, I leveraged satellite imagery and machine learning to analyze $5 million worth of mangrove tree restorations in Mumbai from the last decade. Through my research, I found that only 50% of Mumbai’s restoration sites have shown tangible signs of growth between 2012 and 2022.

I was inspired to pursue a project in Mumbai after enrolling in the India Innovation Studio course at Georgetown, led by Professors Irfan Noorudin and Mark Giordano. The Centennial Lab course examined the social implications of infrastructure and challenged us to critically examine the socio-ecological impacts of international development. The geographic information systems component, taught by SFS alumna Dr. Katalyn Voss, equipped us with the capacity to visualize geospatial data to assist in policymaker decision-making.

Mangrove trees grow along ocean shorelines and are a key solution in addressing the climate crisis. The trees absorb between six and eight times more carbon dioxide than any other ecosystem on Earth.

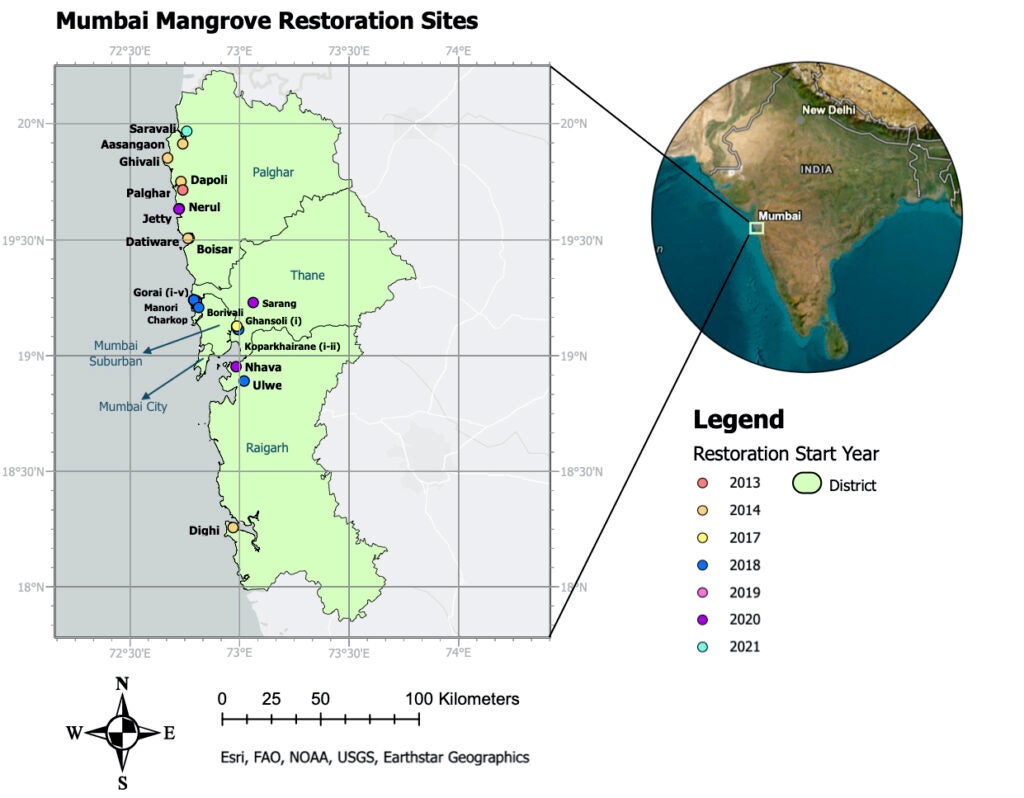

Mangrove restoration locations. Graphic courtesy of Adam Shaham.

In addition, mangroves provide critical services to coastal cities. Their dense root systems prevent coastal erosion and flooding and act as incubators for young fish nurseries. The trees also have medicinal properties, frequently used by Mumbai’s indigenous Koli fishing community.

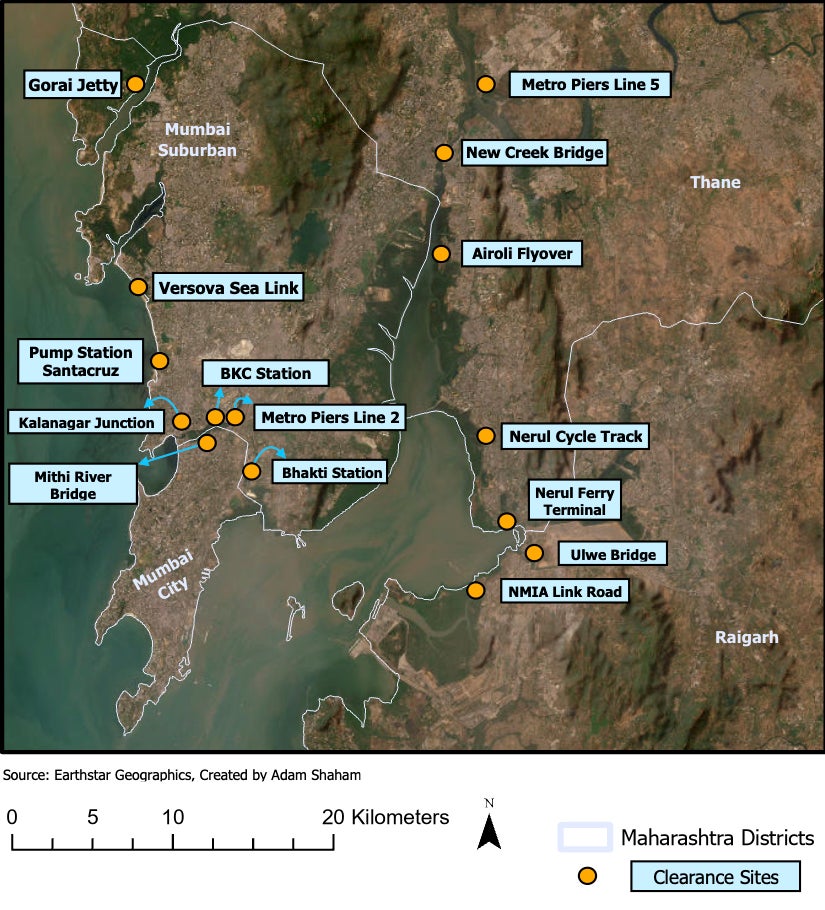

However, rapid urban development has threatened these benefits. Hundreds of construction projects — from new metro lines, airports and ports to bridges and coastal highways — have resulted in the destruction of entire mangrove forests in Mumbai. Mangrove clearance has threatened the local fishing economy and left the city’s communities at increased risk of fatal flooding events.

In light of the trees’ ecological significance, Mumbai’s mangrove restoration initiatives are mandated legislatively. Laws, such as India’s Coastal Regulation Zone, and judicial orders from the Bombay High Court require the municipal government to restore many of the mangrove trees that it cuts down.

Map of Adam’s research clearance sites. Graphic courtesy of Adam Shaham.

Map of areas of fishbone mangrove restoration. Graphic of Adam Shaham.

Restoring mangroves is easier said than done.

Globally, researchers have found that around 50% of all mangrove restoration projects have failed. Attempted restorations in nearby countries like Sri Lanka, the Philippines, Vietnam and Pakistan yielded lackluster outcomes. Single-species planting of mangrove saplings and low levels of community engagement typically doom even the most well-funded and long-term efforts.

Scientific monitoring of mangrove restorations helps to combat failure by identifying unsuitable sites and ineffective techniques. Yet the Maharashtra Mangrove Cell, the state government body responsible for restorations in Mumbai, does not publish the locations of restoration sites. This limits the capacity of environmental nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and scientists to evaluate restoration efforts and recommend improvements.

To determine how Mumbai’s mangrove restorations have fared, I drew on public environmental clearances and federal budget details from India’s Ministry of Forest, Environment and Climate Change. I identified 25 sites covering more than 150 hectares of attempted mangrove restorations in the Mumbai region and created a dataset of restoration site coordinates.

Equipped with geographic information system (GIS) skills and public satellite data I gathered from the European Union (EU) and NASA, I created a machine-learning analysis that investigated Mumbai’s restorations from 2012 to 2022.

The study results indicated that over half — 52% — of the mangrove sites targeted for restoration by the Mangrove Cell in Mumbai showed no sign of growth over the decade. Out of the 157 hectares set aside for restoration, only 30 were successfully restored.

Image of a group of mangroves in the water. Photo courtesy of Adam Shaham.

Thus, Mumbai’s restoration program achieves a success rate consistent with global mangrove restoration efforts — that being that about half of such projects fail. An independent audit of a multi-million-dollar United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) grant that funded some of Mumbai’s mangrove restoration confirmed these findings. The auditors concluded that given prevailing approaches, many mangrove restoration projects in Mumbai were unlikely to become sustainable forests.

Improving Mumbai’s mangrove restoration infrastructure in the future will require a comprehensive transformation of the current approach. The Mangrove Cell needs to publish mangrove restoration locations and more proactively include the local community in restorations. This will promote transparency and accountability for the city’s residents concerning the management of Mumbai’s natural resources.

Currently, Mumbai’s mangrove lands are split amongst the jurisdiction of more than a dozen city agencies. The transfer of all mangrove lands to one agency, such as the Ministry of Forest, would streamline protection and restoration initiatives.

The international community needs to step up as well. Many of Mumbai’s largest infrastructure projects that involved mass mangrove clearance were financed by international financial institutions (IFIs) like the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Japan International Cooperative Agency. IFIs have a responsibility to consider the environmental ramifications of infrastructure projects in their funding proposals and financially support longitudinal mangrove restorations.

Five hundred years ago, mangroves used to cover every inch of Mumbai. Improving the city’s restoration efforts is necessary to ensure that they will return.